How to Solve a (Jobs for Acupuncturists) Problem

nobody asked for my input but hey, that's what Substacks are for

On October 24th there was a town hall/panel discussion for the acupuncture profession about our future. You can watch the recording here. Much of the conversation was about the problem of unemployed and underemployed acupuncturists. The proposed solution was Medicare — because, according to the moderator, “it will result in hospitals hiring thousands and thousands and thousands of acupuncturists” — and also, if I understood correctly, getting advocacy into the curriculum of acupuncture schools.

Back in June I wrote a post titled How to Solve a Problem. Actually, I didn’t write it so much as I took dictation from WCA. Yes, the entity of WCA. It speaks. I try to tone down the woo element in describing what I do (for a variety of reasons — that’s probably a post in its own right, the pros and cons of woo for acupuncturists) but also I’m trying to be truthful and it’s true that WCA talks to me. A large part of my job is to listen as closely as I can.

Anyway, the town hall reminded me of that post, and the whole thing seems like a teachable moment for POCA Tech students (and other people who are interested in our world). Advocacy is an important element of our school’s program, but we try to communicate about it in a very careful, particular way. So this post is going to be a mix of my version of woo with big-picture acupuncture topics like advocacy, job creation, and the future of the profession. All while responding to the town hall. Here goes!

First, though, I want to provide a brief guide to the organizational players in the acupuncture profession. (Thank you to the subscriber who wrote, “if you wouldn’t mind telling us what each of the acronyms stands for, that would be helpful to laypeople like me.” Yes!) I’m continually impressed by the patience our non-acupuncturist readers show for the intricacies of our convoluted little world. In the interests of making this as clear as possible:

NCCAOM: the National Certification Commission for Acupuncture and Oriental Medicine. They create and administer the exams that most states require for licensure. See also, The NCCAOM vs. POCA Tech.

ACAHM: the national Accreditation Commission for Acupuncture and Herbal Medicine. They regulate acupuncture schools. In order to qualify for licensure, you need to attend an ACAHM-accredited school, which is why POCA Tech is accredited.

CCAHM: the national Council of Colleges of Acupuncture and Herbal Medicine. This is the trade organization for acupuncture schools. They also create and administer the Clean Needle Technique exam which students have to pass.

ASA: the American Society of Acupuncturists. They’re the national trade organization for individual acupuncturists; their membership is made up of acupuncturists who are, in turn, members of their state acupuncture associations.

These groups together make up the AHM Coalition, which put on the town hall.

I also want to say, though maybe nobody will believe me, that I sympathize with the kind of behind-the-scenes coordinating work that the AHM Coalition is trying to do. I get how hard it is to create and maintain structures that other people take for granted and complain about. (This is another thing we talk about at POCA Tech, making invisible labor visible.)

But I disagree fundamentally with the AHM Coalition’s approach to solving the problem of jobs for acupuncturists.

The acupuncture profession, unlike the other professions that it’s been trying to emulate and compete with, has never had a solid economic foundation. Years and years of economic data about what acupuncturists earn (or don’t) point to this.1 The acupuncture profession as we know it has been funded by students taking out huge loans to enter the profession, not by acupuncturists making a living and making jobs for other acupuncturists once they’re in it.

Because of the skewed debt to income ratio for graduates, this system is the economic equivalent of a strip mine: It’s brutally extractive and it leaves wreckage in its wake. The wreckage wasn’t obvious until recently — acupuncture graduates tended to blame themselves instead of the system and slink off quietly to manage their life-altering student loans as best they could. That dynamic seems to have changed, though, resulting in a crisis for acupuncture schools.2

What I gleaned from the town hall is that the main acupuncture organizations are now desperately trying to backfill an economic foundation for the profession, via hospital jobs for acupuncturists. Their strategy is to pass federal legislation to get Medicare to pay for acupuncture in hopes that thousands of hospital jobs will materialize just in time to resolve the debt to income crisis. This requires a new focus on advocacy, including via legislative lobbying (with a paid lobbyist), trying to get the acupuncture profession to unify around this effort, and trying to get students involved in advocacy while they’re in school.

Hmm.

POCA Tech students already engage in advocacy while they’re in school, and there are a number of posts on this Substack about the excellent learning opportunities that result. However, advocacy is tricky.

Many students are drawn to POCA Tech by the desire to make acupuncture more accessible, especially to marginalized communities. So we try to be really clear with them from the get-go that they’re not here just to practice advocacy for affordable acupuncture but to learn to make affordable acupuncture actually happen. Which is really different! Learning how to make things happen means learning to give yourself wholeheartedly to projects and problems, which is what the first How to Solve a Problem post was about. It’s a skill set in its own right; it’s also a requirement for success in small business.

Advocacy can blur all too easily into trying to get other people to solve your problems for you and trying to get them to care about things they don’t care about — instead of being willing to befriend and collaborate with your problems yourself, for as long as it takes to generate a solution. Advocacy can turn into symbolic gestures that look good but don’t go anywhere. Plenty of people have mistaken WCA and POCA Tech for symbolic gestures instead of what they are — living responses to certain collective problems — so this distinction is important to us.

Advocating for federal legislation to get Medicare to pay for acupuncture in hopes of solving the debt to income crisis looks to me like an example of that kind of advocacy, as opposed to the kind we want POCA Tech students to practice. So what would it look like to approach this problem our way?

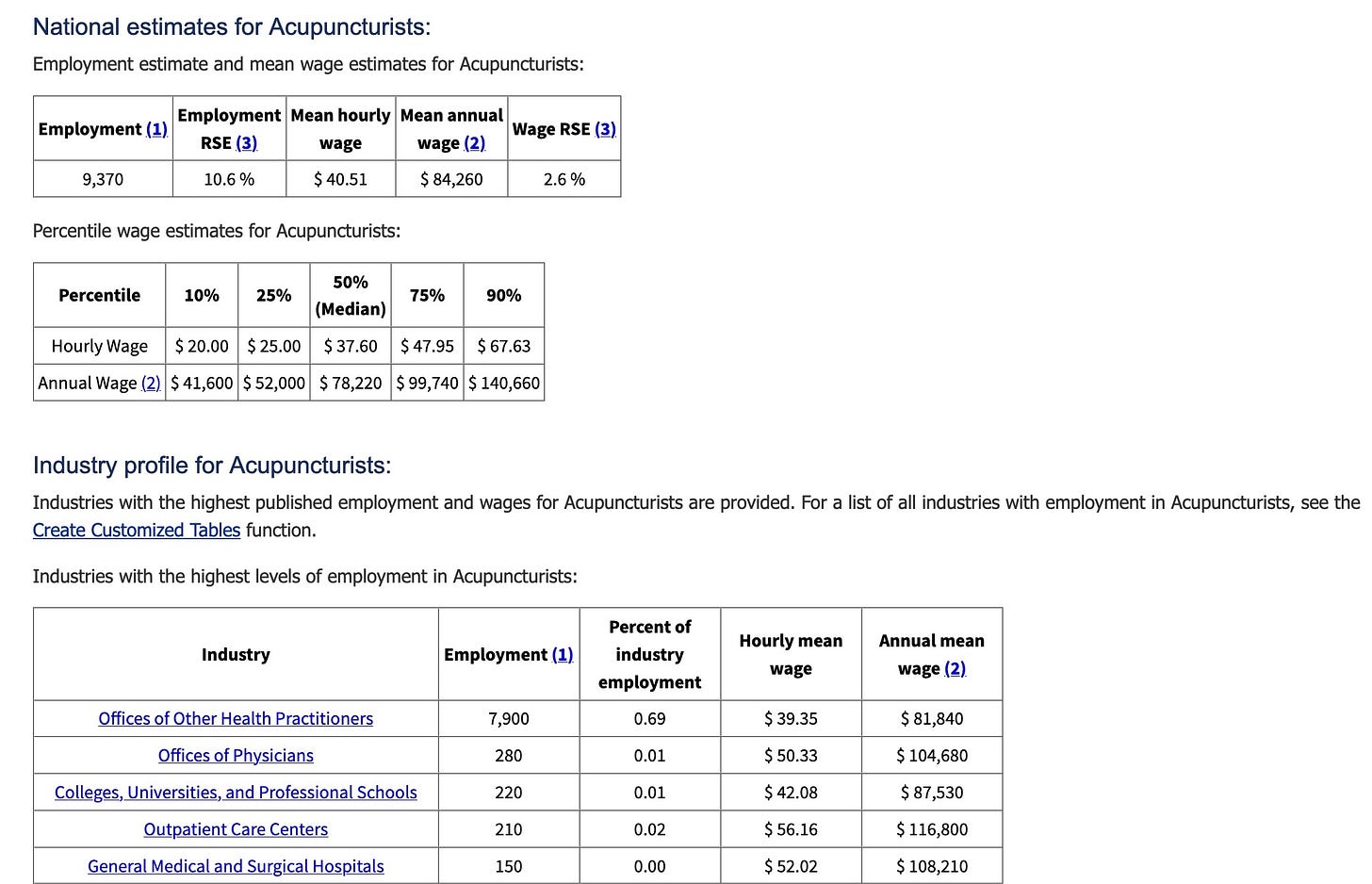

According to the most recent Bureau of Labor Statistics data, there are only 150 hospital jobs for acupuncturists in the US:

I think 150 is a great number — well, not great for the acupuncture profession — but it’s small enough to be manageable and large enough to be meaningful. If this were a POCA Tech project, I’d tell the students to start by tracking down as many of the existing hospital jobs as possible and make a spreadsheet. The next step would be to try to answer these questions: Who are the acupuncturists working in hospitals and how did they find their jobs — networking? Prior connections? What department are they in, who do they report to? How about getting a copy of their actual job descriptions?

And here’s the important part: how exactly is the hospital funding them? What part of the budget do acupuncture services fall under — what exactly is the income stream? How and when was this job created? Who championed it, who made it happen — what steps did they take, in what order? What steps would we need to follow in order to make more hospital jobs for more people? The next phase would be to draft case studies and how-to manuals, and look for opportunities to run a pilot project, maybe in partnership with a willing hospital.

Having created some jobs for acupuncturists, I know that the devil’s in the details. I get why people are hoping that Medicare coverage would generate jobs, but there are many, many steps between “possible funding” and “actual job, that an actual human can fill.” There are so many things that could go sideways, especially in a huge healthcare bureaucracy. Right now we don’t know nearly enough about hospital acupuncture jobs to be holding them out as a wholesale solution. (Is the reason that there are only 150 of them really a lack of Medicare coverage?)

Why haven’t we looked at successful examples that already exist so we can focus on replicating them? Why aren’t we working on spreadsheets and case studies and how-to manuals on creating hospital jobs? And if those spreadsheets and case studies and how-to manuals do exist, why isn’t the AHM Coalition doing everything they can to make them easily accessible?

In other words, why aren’t we putting our best effort into making more hospital jobs, now?

I know this kind of effort is possible, because back in the day, the POCA Cooperative basically did this for community acupuncture. We managed to keep track of 200 some clinics and we knew, in general terms, how their businesses were doing and what factors contributed to success. We tried to make it easier for people to create jobs for themselves by sharing all the information we had. And we learned a lot about what kind of obstacles could arise — for example, we knew Modern Acupuncture’s attempt to scale up and monetize the community acupuncture model was going to fail.

If we collectively want hospital jobs so badly, then why not build a knowledge commons to help us produce them, or at the very least, thoroughly understand them — before trying to massively scale them up? Someone could be working on that while everybody’s waiting for a Medicare bill to pass. How about all those doctoral students who need to produce Capstones?

When you give yourself to a problem, you’re willing to dig into the details and get painfully specific. During the town hall, one of the panelists said, “Every major hospital across the country is exploring whole health and patient-centered care — and acupuncture falls into that.” Sure — but so do any number of other modalities and approaches; “whole health” can mean almost anything. Also, there’s a vast gap between a corporation investigating something vs. actually paying for it. In my experience, all kinds of people are interested in acupuncture and exploring the idea of it, while only a tiny sliver of those are willing to open their wallets, particularly in any ongoing way. For instance, I bet Oregon Health Sciences University would swear they’re committed to whole health and patient centered care — but that didn’t stop them from eliminating all “non-allopathic integrative medicine services” from their budget this summer.

Another panelist noted that passing Medicare legislation could help graduates qualify for student loan forgiveness. Based on some recent discussions, I think a lot of acupuncturists don’t understand how loan forgiveness works. The Public Service Loan Forgiveness program means that if you’re an employee of a qualifying nonprofit organization for ten years, working 30 or more hours per week, and you make payments on your loans the whole time, at the end of the ten years you qualify for loan forgiveness. Again, there are many, many steps between passing legislation and establishing jobs that graduates can work in for ten years — but this doesn’t have to wait on legislation. We could be working on this project now, with resources that we already have.

Again, I know this because POCA already did it. (My co-director at POCA Tech, Jersey Rivers, led the effort.) We even have a CEU on how to how to convert your clinic into a qualifying nonprofit. Five acupuncturists working for WCA have gotten their loans forgiven through PSLF.

Speaking of Capstones, POCA Tech students do them too, often as a group. Advocating for a 5NP law for Oregon was Cohort 8’s Capstone. Advocating for legislation is an amazing experience! I bet actually getting a law passed feels even better! However, as everybody who’s involved in 5NP knows, passing a law does not automatically generate access to treatment for actual humans who need it. There’s additional work required after you have the law you want. Cohort 9 is currently working on a group Capstone project, with the help of our organizational partners at NAYA, about how to create access to 5NP by collaborating with culturally specific organizations. Our hope is to have a detailed road map for implementing 5NP in Oregon even before we have a law, so that we can hit the ground running once we do. But even drafting the road map represents a lot of work, as Cohort 9 can tell you.

Is anybody working on a detailed road map for Medicare implementation? Does it have numbers? Can I see it?

On the subject of numbers, one of the panelists from the town hall noted that the acupuncture profession wants students to get doctorates, and that means that they graduate from school carrying a debt load of $200K to $250K. The rule of thumb for debt to income ratios is that you shouldn’t graduate from school with more student debt than your future annual salary (since that represents a 10-15% payment ratio.) According to the BLS data cited above, the annual mean wage for acupuncturists working in hospitals is $108K. Do we really believe that Medicare inclusion will automatically double the wages of hospital acupuncturists, and that thousands of jobs paying $200-$250K per year will materialize out of thin air in an era when hospitals are looking to slash costs, and physicians themselves are fighting Medicare cuts?

The AHM Coalition just isn’t being realistic. Advocating for Medicare as a sweeping solution to our problems appears to be a symbolic gesture, nothing more (especially when the Medicare bill still has a zero percent chance of being enacted.)

I mean, was the idea of the acupuncture profession ever realistic? Of course 20/20 hindsight is an advantage. But to take a heterogeneous diaspora practice (as Tyler Phan describes acupuncture), cram it into the template that physicians used over a century ago to professionalize their field, and expect thousands upon thousands of upper-middle class jobs to pour out like coins from a slot machine — doesn’t that seem, I don’t know, naive? Idealistic?

(When someone who writes a Substack titled Acupuncture Can Change the World says the profession’s too idealistic, you KNOW it’s bad.)

I’d be inclined to describe the AHM Coalition’s solution as “magical thinking” — except I actually believe in magic. That’s what the original post, How to Solve a Problem, was about: WCA’s particular magic. I also believe that magic has rules, and maybe the most important one is that it’s not just a matter of making symbolic gestures. Magic requires wholehearted participation. That’s what we’re trying to convey to POCA Tech students: when you ask the universe to do something for you, be ready and willing to do everything you can for yourself.

I know because I’ve been complaining about this since 2010. See also, pages 29 to 30 of the California Acupuncture Board’s 2021 Job Analysis.

Thank you for asking about a detailed roadmap for Medicare implementation. I begged for this when I was on the ASA "Medicare Working Group." It fell on deaf ears. The most we could manage was a carefully curated (but non-expert) list of possible pros and cons that we wanted to present to the members, and even that was edited at the last minute before an (arbitrary) deadline to remove any reference to cons.

[Tangentially: Would like to see your thoughts on woo and acupuncturists.]