What Do Acupuncture Points Do?

part one: description vs. prescription

I’ve been trying to write some posts about acupuncture theory for a long time, but it’s been hard to figure out where to start. Certain topics in acupuncture are like that; whether you’re writing or teaching, it feels like you have to circle around it for a long time until you find a way in.1 Until something cracks a door open for you. Two things did that for me recently: the last post, when I wrote about only being able to use a few acupuncture points for one of my patients (but those few points got life-changing results, for him and for me) — and this newsletter by Tara McMullin about descriptive vs. prescriptive content and what she calls the Prescription Economy:

Descriptive content seeks to explain, catalog, or narrate its subjects. It treats subjects with curiosity. When descriptive content presents an argument, it argues for a way of interpreting and making sense of a phenomenon.

Prescriptive content presents solutions, advice, or rules to guide future action. It treats the audience as agents who will act on the topic at hand. Prescriptive content also argues for a way of responding to a phenomenon...

Both descriptive and prescriptive content have valuable uses. One is not better, more rigorous, or more honest than the other...(but) the “literature of self-improvement" is the water in which we all swim today. Especially in our convenience-oriented, service-based market, prescriptions for better living are both perfect marketing and perfect product.

A lot of writing about acupuncture points is the prescriptive kind: this acupuncture point does X; do acupressure on yourself using X point to address X problem. That’s what people expect from a post about acupuncture points; heck, it’s what people expect from a three-year acupuncture program! And they’re not wrong. It’s virtually impossible to talk about an acupuncture point without talking about what you might use it for. (I’m not immune! Ask me how I treat temporal headaches and I’ll tell you about Heart 8; I once treated a patient with terrible chronic migraines and I managed to save him a trip to the ER and a Demerol shot by needling Heart 8, along with Gallbladder 34 plus threading Forehead-Temporal-Occiput on the earlobe. I can’t think about Heart 8 without remembering what it did in that particular case.)

Prescriptive content about acupuncture points isn’t wrong but neither is it complete, so it can be misleading. Suggesting acupuncture points as a means of self-improvement and/or turning any discussion of them into “perfect marketing and perfect product” — that’s what our self-improvement-obsessed consumer society encourages but it’s not what WCA and POCA Tech are trying to do. Since this newsletter is all about sorting through what exactly we’re trying to do, here’s a post about acupuncture points from a descriptive rather than a prescriptive angle.

Let’s start with the phenomenon we call the herbalization of acupuncture.

As I never tire of reminding everyone: There is not now, and indeed there has never been, one right way to do acupuncture. However, in the US there is a standardized way to do acupuncture as defined by Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM). Standardization is part of regulation and professionalization, which are both fraught for acupuncture in the US. (If you’re new here, check out this interview with Tyler Phan Ph.D about how acupuncture is a blob, and blobs are hard to regulate!) Herbs are very important in TCM. I went to an American TCM school, so when I learned about acupuncture points, I learned about them as if they were herbs.

In TCM, herbs have functions. For example, Rehmannia (Shu Di Huang, 熟地黄) nourishes Yin and Blood, tonifies the Kidney and the Liver, replenishes Kidney Essence (Jing), and calms the Shen (spirit). That’s what Rehmannia does. You wouldn’t give Rehmannia to someone who didn’t need some kind of tonification. A lot of TCM diagnosis is about figuring out who needs what (tonification vs. sedation, cooling vs. warming) using the tongue and the pulse.

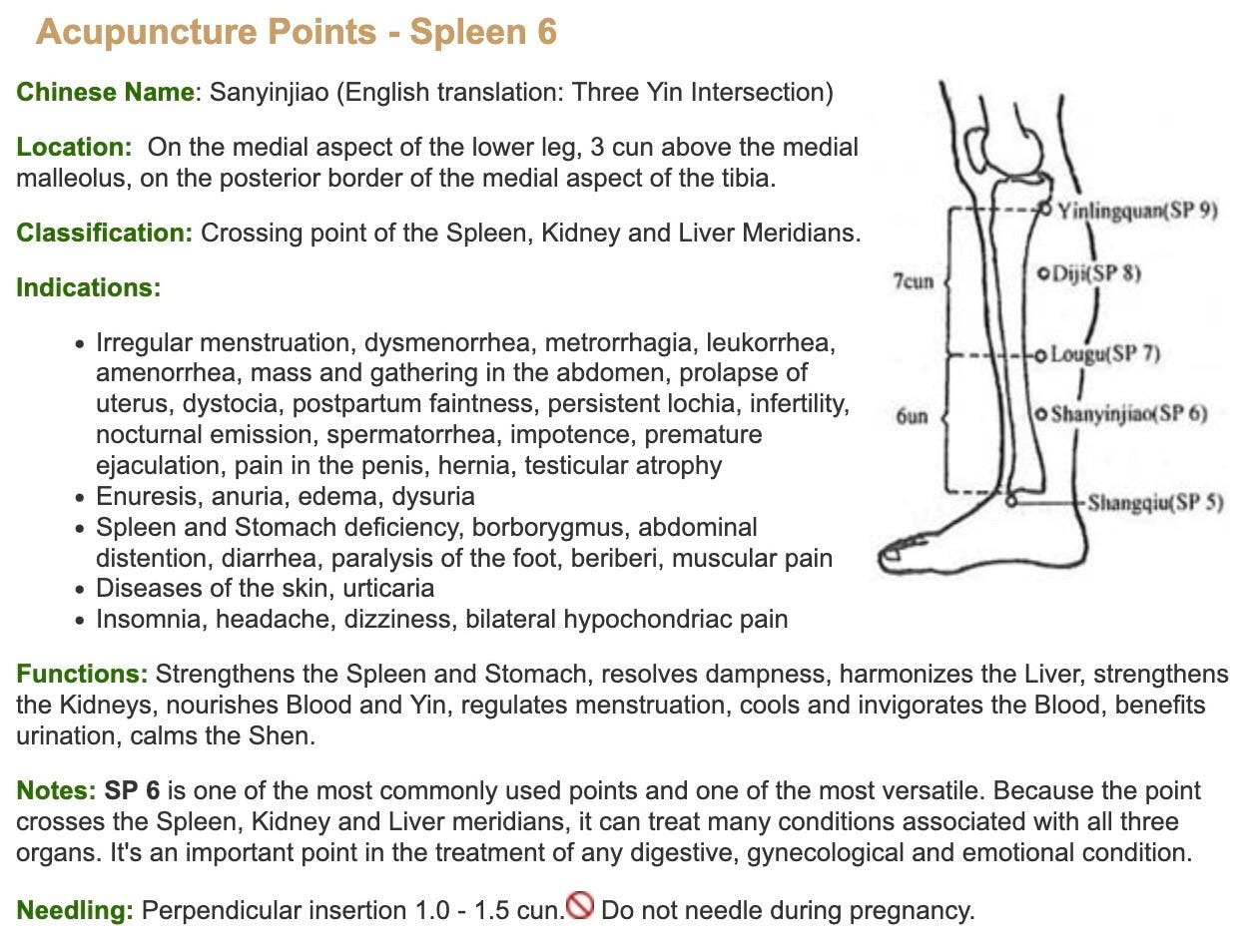

Similarly, in TCM, acupuncture points have functions. Like Rehmannia, Spleen 6 strengthens the Kidneys, nourishes Yin and Blood, and calms the Shen. In TCM school, I learned that I shouldn’t needle Spleen 6 on someone unless I had done the appropriate tongue and pulse diagnosis to determine whether they needed to have their Kidneys strengthened and their Yin nourished. I learned that if I didn’t match an acupuncture point’s functions to a patient’s TCM diagnosis, I’d be giving them the wrong treatment.

That’s an example of the prescriptive content of a TCM school — or maybe most acupuncture schools? And it’s not wrong. It’s definitely what students want from school, they want to learn the rules. But after I graduated, I found to my chagrin that my patients weren’t aware of those particular rules and indeed, their bodies had no obligation to follow them. The people I was seeing didn’t fit into neat TCM diagnostic patterns and their responses to acupuncture didn’t, either. And so my experience of acupuncture practice was more like being part of an unfolding narrative. Orienting myself toward curiosity served me better than orienting myself towards giving advice.

When the narrative took an unexpected turn, with a patient who basically got up off his deathbed apparently as a result of what my acupuncture school would’ve said were wrong treatments (lots and lots of wrong treatments)2 — I was amazed and grateful, of course, but also sort of exasperated. Okay, fine, so much for the rules! I gave up on trying to follow them and applied myself to figuring out how acupuncture could be adapted to my community.

The herbalization of acupuncture didn’t particularly serve my community (more about that shortly). And really, the herbalization of acupuncture is pretty questionable once you start thinking about it. Why would acupuncture points have functions in the same way that herbs have functions? Rehmannia, which you put in your mouth and swallow, is obviously not the same kind of thing as Spleen 6 — which is a place on your leg. Rehmannia is an external substance that you take into your body while Spleen 6 is part of your body.

And the body is a mystery, full stop. There’s no amount of prescriptive content — advice, rules, etc — about acupuncture or any other kind of medicine that will make the body NOT a mystery, that will eliminate the need for descriptive elements like interpretation, curiosity, and narrative.

When I was in acupuncture school, I remember a teacher telling my class with some asperity: acupuncture points are not buttons! From my vantage point now, I imagine he was wrestling with what feels like a reductive approach to acupuncture points: use X point for X problem. Just push here and your nausea will go away! The problem is, that does actually happen sometimes. That’s why you can buy Sea-Bands at Walgreen’s, because sometimes acupressure on Pericardium 6 works just as well as anti-nausea medication. It’s why ear seeds for 5NP are a thing, because pressing those points on the ear can reduce drug cravings. Push here, get relief.

But acupuncture points aren’t like buttons in the sense of: be careful because if you press the wrong button, something somewhere in the body might blow up! Or short-circuit, or otherwise malfunction. Nonetheless, in acupuncture school, I did get the impression that acupuncture points have some button-like aspects in what felt to me like the machine of TCM diagnosis: Spleen 6 is the button for nourishing Yin. Don’t press that button if your patient doesn’t need more Yin! This is where the herbalization of acupuncture can be misleading. You absolutely can make someone worse by prescribing the wrong herbs. You need a TCM diagnosis with herbs so that you don’t exacerbate an imbalance of heat or cold, excess or deficiency.

But can you do that by needling an acupuncture point?

Based on my experience: no, you can’t. It’s not like pressing or needling Spleen 6 releases a flood of extra Yin somewhere. (Also, Yin isn’t something that you actually measure.) This is important not only for theoretical reasons but for political ones: what you believe that acupuncture points can do inevitably connects to how you think acupuncture should be taught and regulated. If you believe that an acupuncturist can cause actual harm to a patient by needling, say, Spleen 3 when they should have chosen Spleen 63, well, maybe that justifies entry-level doctoral degrees along with a lifetime of crushing student debt? I’m starting to wonder how much the prescriptive element is responsible for our debt-to-income crisis.

I’ve written elsewhere about how some acupuncturists think the simplicity of what we do at WCA and POCA Tech is bad, because acupuncture is supposed to be part of “a complete system of medicine”. Focusing on acupuncture by itself, without herbs or other bodywork or lifestyle advice (especially lifestyle advice), is somehow diminishing. Or as Peter Deadman suggested, the community acupuncture model impoverishes Chinese Medicine. And certainly my TCM school taught me that acupuncture by itself isn’t all that great.

So imagine my surprise, circa 2001, when my patient was kicked off of hospice apparently as a result of me practicing the most diminished, impoverished version of the “complete system of medicine” I’d been taught. I was treating my patient without benefit of a TCM diagnosis because there was no point in having one; he’d only let me needle a handful of points regardless. What I took from that experience was that acupuncture actually is pretty great, and also it doesn’t need to be herbalized — sometimes it’s better if it’s not? Maybe acupuncture that isn’t herbalized can be more flexible, more creative, and more adapted to people in my community who can’t actually afford the “complete system of medicine”?

And possibly it’s just as effective or (gasp) even more effective? (Pro tip: acupuncture that people actually get is approximately 1000% more effective than acupuncture that they don’t get, even if it’s theoretically purer.4 ) This seems like a good example of the kind of freedom that description can offer but prescription can’t.

I’m kind of in love with this descriptive vs. prescriptive analysis so you’ll be hearing a lot more about it. Next up: more about what acupuncture points do, and how POCA Tech teaches acupuncture without herbalizing it.

This “where do I start?” phenomenon is also frustrating for acupuncture students, especially first year. Learning acupuncture is not unlike learning a language, where it feels like you’re just memorizing lists of unconnected words for a long time before something finally clicks, it all starts coming together, everything actually means something and eureka, you understand! But the memorizing lists part is dull, and the feeling of circling around something enormous that you can’t find your way into isn’t fun either. We always tell students that the first year of acupuncture school is something you just have to slog through, on your way to the good part — which is clinic.

Also (as I’ve said previously) some topics in acupuncture are charmingly frustratingly recursive. What’s the definition of an acupuncture point? It’s where you stick an acupuncture needle. What’s the definition of acupuncture? The practice of sticking needles in acupuncture points.

And it wasn’t a one-off. At least three other WCA patients that I know of have had similarly startling results: If Your Patients Aren’t Breaking Your Heart, Are You Really Doing Community Acupuncture?

To fend off arguments from acupuncturists, I’ll reiterate: to the best of my knowledge there is no robust research on the relative efficacy of different styles of acupuncture let alone the relative efficacy of Spleen 3 vs Spleen 6. If you know of any solid studies that compare the efficacy of, say, TCM with Five Element Acupuncture or Japanese Acupuncture or literally anything else, please send it to me. Similarly, if you want to argue about the efficacy of community acupuncture vs. conventional acupuncture, send me research! On that topic, I thought this study was interesting: Group versus Individual Acupuncture (AP) for Cancer Pain: A Randomized Noninferiority Trial: “Group AP was noninferior to individual AP for treating cancer pain and was superior in many health outcomes. Group AP is more cost-effective for alleviating cancer pain and should be considered for implementation trials.”

See also: Acupuncture for Heretics.

On the nail. I’ve remembered your story about the client who limited your needle sticks with astounding results, read it in a book years ago. As a worker who has benefitted from Medicare several decades, tried to get out for decades too, I recognize societal push to prescribe instead of curiously describe. Medicare demands justification and documentable progress—it won’t pay for curiosity. Grad school taught me research methods “quantitative” vs. “qualitative.” Blind control vs. narrative. But narrative doesn’t pay. WCA always feeds my hope of seeing how to do something healing and still remain housed. Love reading your comprehensive posts and please keep shouting out.