The Real and the Unreal

and how to make an acupuncture school on a shoestring

Recently one of our paid subscribers wrote: “I admire the concept behind POCA Tech and how it offers a more financially feasible path for future acupuncturists compared to (other institutions). I'm interested in establishing a similar school... one that prioritizes affordable tuition and allows students to continue working while studying. I'd appreciate it if you could share some of the major obstacles you encountered during your journey, and if there's anything you would have approached differently in hindsight.”

I thought, what a great writing prompt! And then I tried to answer the question. Three drafts later I thought, shit.

This newsletter has been amazingly useful for me, WCA and POCA Tech in so many different ways (more about that here). But in other ways it’s totally not gone to plan. I wasn’t intending to write about the acupocalypse -- like, at all. I was trying not to write about it. And I felt I had written plenty about CPTSD (my own) here and here.

But there’s no way for me to write about the obstacles to making an acupuncture school without getting into both of them. Again. So here goes. Content warning for CPTSD and related topics.

In hindsight, the primary mistake I made with POCA Tech was to downplay the brutal amount of work it required. I had some good reasons for that: Even a tiny little acupuncture school is a huge, complex, bureaucratic project that unfolds over years. It requires stamina; it’s not a good idea to think about how steep the hill is while you’re in the middle of climbing it. POCA Tech was essentially a group project between two organizations, the POCA Cooperative and WCA, so a lot of people were involved in a lot of different ways, particularly fundraising (more about that in a minute). When you’re starting an acupuncture school from scratch, a whole lot of stakeholders have to take your word for it that you’ll deliver — because they’re entrusting you with significant amounts of their money and their time. You have to put a lot of energy into those relationships; keeping people informed and enthused is a big part of the job.

I downplayed how hard it was to make a school both because I knew that plenty of people in the acupuncture profession were expecting and hoping that we would fail, and I didn’t want to give them ammunition — and also, I didn’t want the people who were pouring their time, energy and resources into the project to lose heart, which would have been easy to do.

So if you want to make an acupuncture school, here’s my 20/20 hindsight advice: get REALLY honest about the grueling difficulty of the task. Ask yourself: how badly do you want this? What exactly is driving you to attempt an undertaking that might charitably be described as bananas — and how hard are you willing to be driven?

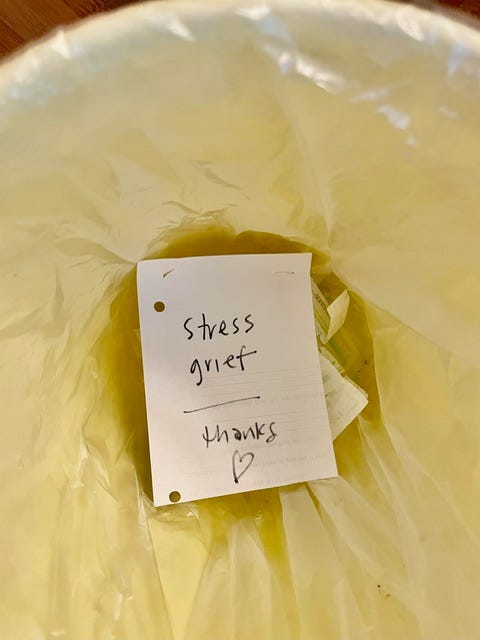

Sometime around 2002 I realized I had a choice between 1) letting my trauma history destroy my life or 2) using it as fuel for…something. I had learned there was no way to avoid it, so I needed to figure out how to live with it. That required finding a receptacle for an overwhelming amount of rage and pain, which on some level was just raw energy. (The rawest.) I needed something to pour it into.

Hmm, how about a bottomless pit of invisible labor?

For whatever incomprehensible reason, making institutions is my thing. The bottomless pit of invisible labor required to make, first, a big clinic like WCA and later, an accredited acupuncture school, turned out to be a great place for me to put all that energy. Eventually I got tired of the invisible part (that’s a different post) but the bottomless pit itself was exactly what I needed. It was not unlike burying nuclear waste — if the nuclear waste was still on fire.

But the problem with invisible labor is, well, how invisible it is, and as a result, how much people can take it for granted. How can I put this delicately? There is no way to pay yourself, or all the other people you’ll need to help you, anything remotely in line with the work required to make an affordable acupuncture school.1 Is working for free — in ways that nobody can see, for years on end — going to be good for you?

We began fundraising before POCA Tech opened and we were able to raise almost $200,000 for the school’s start-up phase, much of it in small donations. For the next five years, POCA continued to pay POCA Tech’s accreditation costs, along with some generous grants from organizations like the Franciscan Sisters of Perpetual Adoration. (If you’re wondering why an order of Catholic nuns would donate $40,000 or so to an acupuncture school, read this post about Liberation Acupuncture.) And even with all that fundraising, POCA Tech wouldn’t have been possible if WCA hadn’t donated its facilities and clinical supervisors, to the tune of $45,000 in-kind per year, every year — and if a lot of people hadn’t poured thousands and thousands of hours of free labor into the school, and if I hadn’t spent thousands more coordinating the process. Even with that volume of donations, we were still renting classrooms from churches and otherwise running POCA Tech on a shoestring.

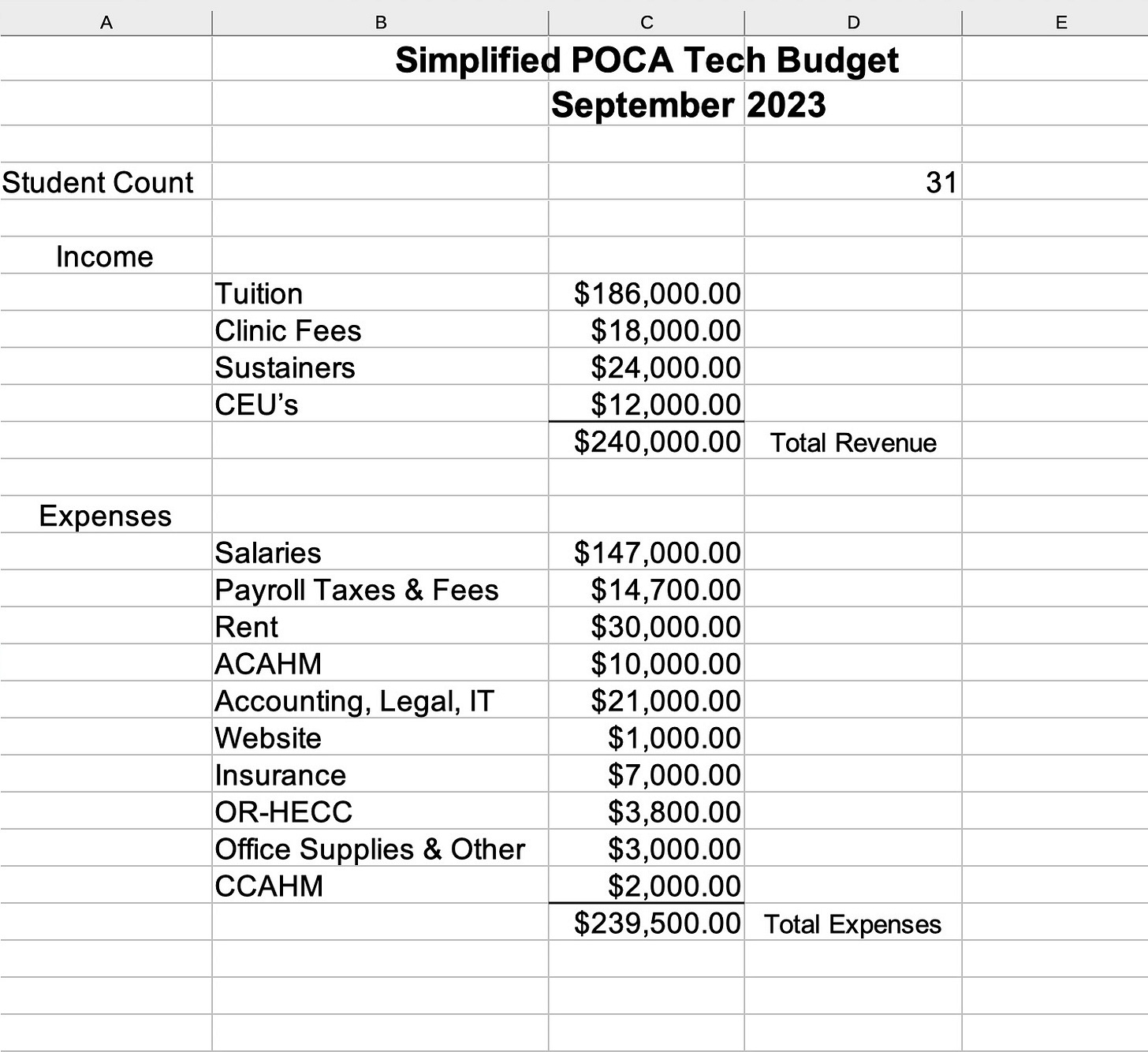

By which I mean, we’ve been graduating 10 or so students per year on an annual budget of less than $250,000 for a three year program. This seems like a good time to share a rough outline (most numbers are rounded, some things are left out — like in-kind donations from WCA and Away Clinics — but you can see the overall shape of the thing):

You’re probably thinking, can those salaries/payroll numbers be right? When I share our school’s finances in public, there tends to be some screaming about POCA Tech staff — all of us — getting paid $21 an hour or so (no benefits). Like how can such a thing exist, we’re devaluing everything, we must be money-hating martyrs!

No, we just did the math. I didn’t realize, before I started a school, that the math for acupuncture education is grim and the math for affordable acupuncture education is worse. We do know what grants are and yes, we have applied for them. We fundraise all the time, more than any other acupuncture school I know, and we have wonderful, committed donors, many of whom have been giving regularly to the school for a decade now. Spoiler alert, we’re getting ready to do a summer campaign. If you’d like to become one of our wonderful donors, please feel free to contribute to POCA Tech here. (And if you’re outraged by our budget, I’d be delighted if you chose to express it via a donation as opposed to angry emails).

One cool thing about running an organization on a shoestring is that every donation really does matter, regardless of size. A $25 donation pays for an hour of my salary. Of course I’d like to make more money (who wouldn’t?) but remember, I fought for my life and I won. I’m not complaining.

Which gets us to the next obstacle I wanted to address: One of the most challenging aspects of participating in the business of acupuncture education is the disorienting mix of the real and the unreal.

Quick digression so that I can talk about Ursula K. Le Guin for a moment, which I always want to do. A decade or so ago, Saga Press published a collection of her short stories, The Unreal and the Real:

I just wanted to say: everybody should read it.

Anyway! A primary feature of CPSTD for me is dissociation. I used to be very dissociated, and receiving acupuncture was a major part of changing that. Later, when I got less dissociated, I also got less functional for awhile. Which is tricky if you live in a country with no safety net. Figuring out how to not be dissociated but still functional has been a project for my entire adult life — which, not coincidentally, has overlapped with being an acupuncturist. I’ve spent decades trying to figure out what’s real, versus what’s not, about myself and my history — and also about acupuncture.

Here’s an abbreviated list of what’s real and unreal about acupuncture:

Real: Acupuncture helps most people but not everyone (nothing helps everyone). Sometimes it literally saves people’s lives. People need different amounts of treatment to get results, depending on what they’re being treated for. Some of the people who benefit the most from acupuncture are the least able to afford it, even on a sliding scale. Acupuncture for the most part is quite safe but it also requires the practitioner to pay attention to safety in a way that many people aren’t prepared for. Placebo is involved, in a good way. Acupuncture isn’t rocket science…

but it can do a staggering amount of good in a community.

Unreal: “it’s a growing profession”; “it’s a lucrative career with a median income of $72,000”; “acupuncture is equivalent to Traditional Chinese Medicine”; “acupuncture by itself doesn’t work without herbs and lifestyle counseling”; “only acupuncturists with at least 2000 hours of training can safely handle acupuncture needles”.

Let’s look at an example of acupuncture unreality involving math. Recently an industry group quoted the statistic of “more than 10 million acupuncture treatments are administered annually in the United States”. Sounds great, right? Very legit!

Actually it’s terrible. (Unless the “more than” means “ten times more than”. For the purposes of this exercise I’m going to assume “more than” means something like “10 million and change”, and I’m going to ignore the “and change” part since I don’t know what it is.)

Let’s assume that all of those treatments are provided by licensed acupuncturists, which is definitely not true (chiropractors, MDs, and others can legally practice acupuncture in many states). According to my friend Whitney, who is a huge nerd about this topic, there are 33,778 licensed acupuncturists in the US. Let’s assume all of those people are practicing, which is also definitely not true. 10 million divided by 33,778 = 296 treatments per acupuncturist annually, or just about 6 per week with 2 weeks’ vacation. Someone with deep knowledge of the industry told me, circa 2004, that the average number of patients an L.Ac sees per week is 12. This is not a new problem.

From there you can do the math a couple of different ways. If an acupuncture treatment nets an acupuncturist on average $100, let’s see — that’s $29,600 in gross annual income. Or you can calculate individual patients. Years ago, WCA did a quick and dirty survey to figure out the average number of acupuncture treatments per patient and the number we arrived at was 6 treatments per person — which makes sense if you consider the range of patients who get acupuncture multiple times a week, every week vs. the people who tried it once and decided it wasn’t their cup of tea. So let’s divide 296 treatments per year by 6 and we get 49 individual patients per year total, per L.Ac in the US. Crunching the numbers another way, there are 336 million people in the US. If even 5% of them were getting 6 treatments per year, that would be 100.8 million treatments as opposed to 10 million.

The business of acupuncture education is a place where reality collides with unreality all the time. Most things about the culture and the structure of acupuncture education reflect a decision that it should be hard to get an acupuncture license, because acupuncture from licensed acupuncturists is in demand! But acupuncture from licensed acupuncturists isn’t in demand and never has been, not unless you do a huge amount of (probably unpaid) work to make it accessible, or you somehow get lucky. Having a school will force you to confront this disconnect constantly — but making a school will not in and of itself create demand for your graduates’ work. They’ll have to do that themselves.

The reason it’s been worth it to me to keep navigating the collisions of reality with unreality is because that’s something I was doing anyway, something I’ll have to keep doing for the rest of my life, to manage CPTSD. The unreality and unsustainability of acupuncture as a profession (in the way it’s currently structured) are becoming more and more unavoidable for everyone. What’s your plan for your school to survive the coming acupocalypse? When the rest of the profession won’t even admit it’s happening, maybe because they can’t handle the reality? Maybe they’re all dissociating?

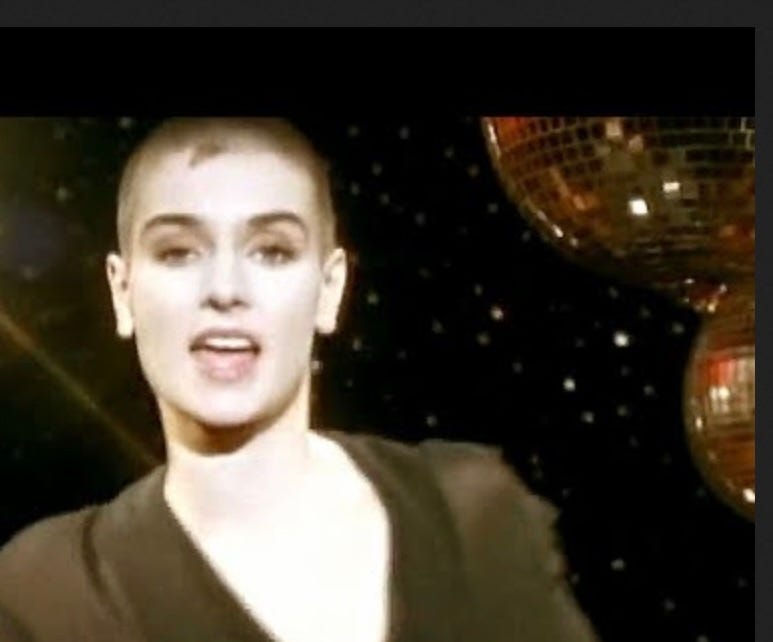

I wish I had a more upbeat answer to your question. To quote Sinead O’Connor:

Maybe it sounds mean/ but I really don’t think so/ you asked for the truth and I/ told you… /

We’ve got a severe case of the emperor’s new clothes.