Thank you to everyone who read the last post and said nice things. I confess I’m surprised that people are curious about the bureaucratic nuts and bolts of making an acupuncture school. But since you were up for that, let’s see if I can interest you in the flip side of all that structure: the part that’s about trying to prepare students for the absence of structure after they graduate. Hello, small business.

Everything you have to do to get an acupuncture school licensed and accredited, the mountain of documents and all the evidence of planning you have to show your regulators, is about reducing certain risks for students when they enroll (at least in theory). Particularly, the risk that your school will suddenly run out of money and leave them stranded1, and/or the risk that they won’t learn what your school purports to be teaching. I’m not arguing with those requirements. However. In the context of an industry where there’s almost no employment after graduation, all that structure and all that risk-reduction can be deceiving, because it makes the acupuncture profession look more solid than it is. (See also: a school that’s part of the Educational Industrial Complex is not a key for graduates to unlock the Healthcare Industrial Complex and its jobs.)

So if POCA Tech is serious about preparing students for the unprotected, uncertain life of a small business owner (or employee) after graduation — and we are serious, you might’ve noticed I never shut up about this — how can we create safe (and legal!) opportunities for students to learn to tolerate risk while they’re still in school? Because, as one student put it recently, this acupuncture business thing is not for the faint of heart.

Let me tell you about our 1000 X 25 exercise: what we learned from collectively trying to ask 1000 people to donate $25 to POCA Tech (each student was required to ask 30 individuals). As I mentioned previously, some students hated it. If I’d had to do something like this when I was in acupuncture school, I would’ve hated it too. Here’s an excerpt from another student’s reflection paper:

Gosh, I did not initially enjoy the idea of this activity. I resisted it. I procrastinated. I squirmed trying to figure out if there were possibly any ways I could get out of it (can I just make a big enough donation to cover this myself??) I finally made a deal with myself that I would just write out the names of all the people I was connected to enough that I could possibly ask. Just to see, how many people do I know?…We had a class with Lisa about this assignment, and I left feeling so inspired and energized and empowered to go ask my people. It was as if the clouds had lifted and it all just sounded so easy. But several hours later, when I was back home and facing the need to actually do the task, instead of daydream/fantasize about it, I returned to the space of intense resistance. It seems like it is easy for me to get inspired and motivated about things, but maybe just as easy to become discouraged, unfortunately.

I did find that having a limited amount of time to execute this task was essential. I needed that time pressure to force myself to act. I respond pretty well to deadlines and I think things would have stretched out indefinitely without one. I also realized it is extremely helpful for me to do one step at a time, even if the step is really small, when I’m approaching something I don’t want to do. In this case, I did the single step of writing out a list of names. I waited a few days. I took a second step of drafting a letter, putting in screenshots and pics, writing from my heart. It was easy to write the letter about community acupuncture and my school. I had a lot that I could say, I wasn’t trying to be anyone in particular and felt I could write in my own voice. I am a solid writer and I communicate most effectively in writing anyway, so that part was enjoyable. The letter sat in my email drafts for a while. I slowly added recipients to it. There came a day when the only task was to click the “send” button, and clicking a single button is really easy.

I love this paper for how clearly it identifies one of the crucial skills of small business: the ability to keep moving yourself forward, one small step at a time (possibly with breaks in between) when your inspiration has fizzled out and you’re faced with tasks that intimidate you.

Another theme that came up repeatedly, even for students who found the exercise easy to do, was the theme of support and connection. As in, how much support do I really have vs. how much support do I need? Am I connected to my community and will they show up for me? These are terrifying questions. They’re the questions that arise in the early stages of an acupuncture practice when your waiting room is empty and your schedule is empty and you feel like you’re staring into the abyss. I don’t know anyone who hasn’t had at least some of those days, and most people have more than some, at the beginning. It can feel like rejection — like the whole world is rejecting you. It can stir up a nauseating mix of shame, dread and disappointment. So it’s not surprising that people give up, thinking if they feel that bad about their practice they must be doing something wrong, or maybe they’re just not cut out for this.

School can be hard in a variety of ways but the very structure of it means it usually doesn’t quite feel like that. As I said in the last post, even a bad acupuncture school is still a community, on some level; it’s usually giving its students something to do and — crucially — people to do it with, so it doesn’t prepare you for the feeling of being out on a limb all by yourself, staring into nothingness, with no structure except the structure you make for yourself.

I don’t think acupuncturists’ introduction to those particular challenges should come after they’ve graduated and they’re really and truly out on their own. As hard as this exercise turned out to be, I’m relieved that now we have a way to simulate the emotional conditions of a brand new practice, so that students can begin to develop some tolerance while still having the support of their peers. I wish we’d thought of this ten years ago.

An inevitable part of running a small business, in my experience, is that people will sometimes disappoint you. A promised stream of referrals never comes through; a planned collaboration falls apart; people don’t show up on the day you need them to help move your furniture. A number of students described feeling disillusioned by the 1000 X 25 exercise. They discovered that some people who had said they were excited and supportive for students’ career paths, when asked for a tangible expression of their support, couldn’t be bothered. Often it wasn’t about the money itself (most students asked for $25 “or a donation of any amount, everything helps!”) It was painful to learn that certain relationships that students thought were reciprocal, relationships where they had given support in the past, didn’t go both ways.

A number of people, including me, encountered situations where they asked someone for support and they wished they hadn’t. I’m pretty confident the person with whom I had the most memorable version of this doesn’t read this newsletter, so I’m going to go into a little more detail: I asked someone to donate $25 to POCA Tech who has, in the past, been vocal about what a great idea the school is. Money definitely isn’t an issue for them (they’re vocal about that too). Their response to my request was to offer me something different than $25, something they thought the school could benefit from — but that would have required a bunch of work from me. One thing I’ve learned over the past decade or so is to make my invisible labor visible, otherwise I’ll get eaten alive. So I explained why their alternate offer was going to be difficult and time-consuming to implement — and then the conversation got weird. (And not in a good way.) In the space of an hour or two, going back and forth over email, I learned some things about this person that I’d rather not know. It was the kind of interaction that can leave you thinking, “Asking for help is a mistake, it’s not worth it, I’ll never do that again.”

Of course I talked about it with students in our leadership classes — coincidentally, at the same time we were unpacking the amazing progress we’ve had with our 5NP legislation. All of that progress is the direct result of asking for help over and over, in every direction. The take home message is yes, some people will let you down — but some other people will blow your mind with their generosity. You don’t know what will happen until you ask. If you want to do anything big, you have to learn to ask and keep asking even in the face of disappointment.

You also have to learn to think about success and failure in a loose, non-binary kind of way. One of the first questions people tend to ask about a fundraising drive is, did it succeed?

Overall POCA Tech acquired more than 280 new donors, which is a lot! Furthermore, dozens of donors, both new and recurring, were overwhelmingly supportive. (Including many of you who are reading this newsletter — thank you!) People gave much more than we asked for and/or they gave much more than we would’ve expected, given their circumstances. Because of the way our fundraising platform works, it wasn’t always easy to identify which donors were responding to students asking for donations, but my estimate is that the 1000 X 25 exercise generated more than $16,500 in revenue.

But wait, isn’t that a failure? To aim for $25,000 and hit $16,500?

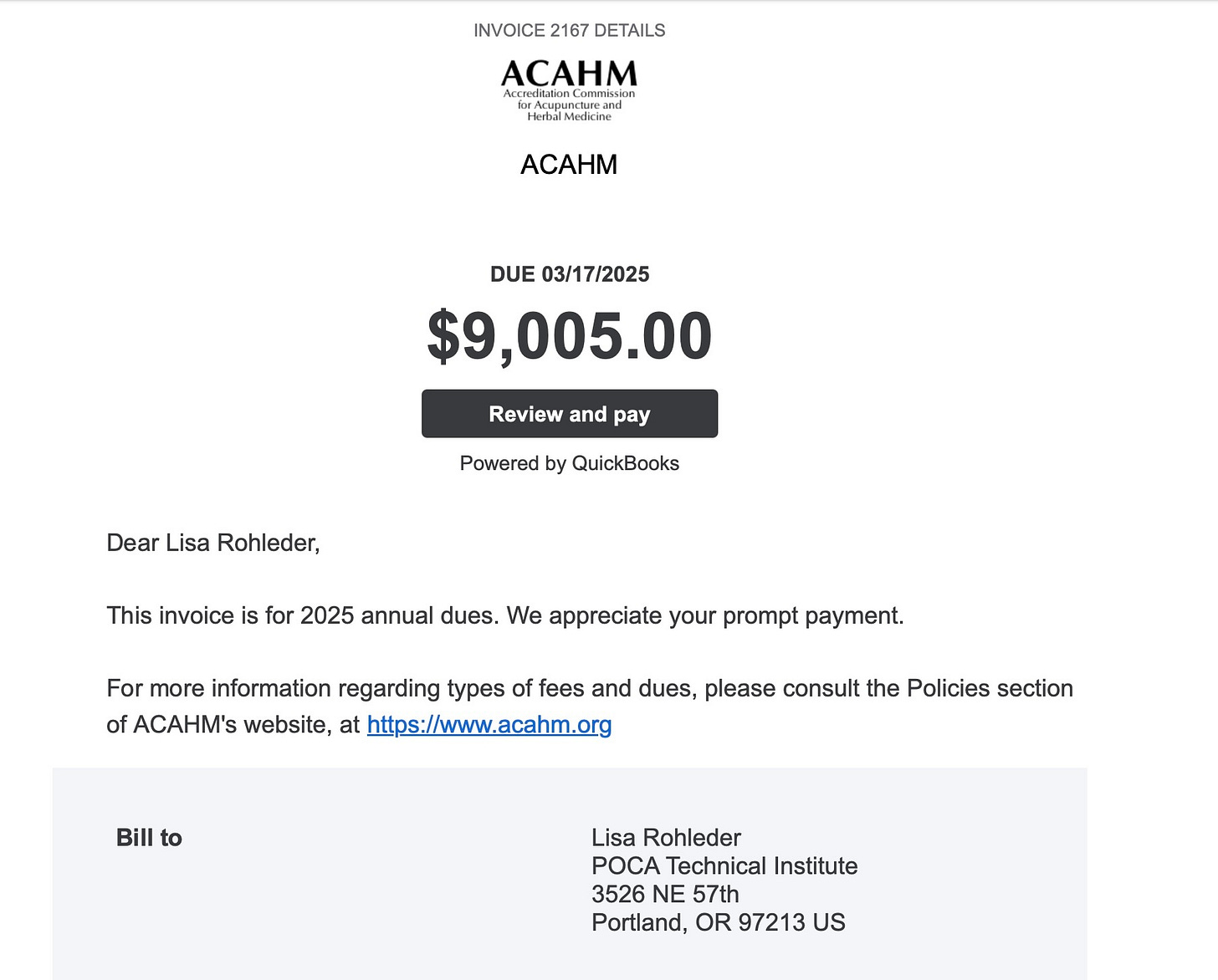

Our goal for the fundraiser was to cover some of the bureaucratic costs of being an accredited school: the yearly cost of our state licensing fee plus annual dues to remain accredited by ACAHM, $11,000; the yearly costs of specialty accounting for accreditation (we can’t just do our taxes like a normal business, they have to be audited or reviewed), $8000; the accreditation costs related to a special site visit because we moved our classroom, $3500 — which gets us to $22,500, and then we rounded it up because we were worried about our heating bills.

We easily covered all of our accreditation costs, which was a huge relief. This is what an accreditation invoice looks like and usually they make my heart sink. It was a great feeling to open this particular email and know that there was plenty of money in the bank to cover it:

When we were talking about the success/failure question in class, I told the students that I felt so optimistic as a result of covering the accreditation expenses that I had a little burst of energy to tackle the part about specialized accounting — the $8000 for a CPA to do a review of our financials. (The story of POCA Tech and our various CPAs is so long and convoluted I can’t go into it now, but I might in a future post.) We’ve had many disappointments in the past with this part of our operations. After the fundraiser, though, I woke up one day and thought “I feel lucky” — so I went CPA-hunting (again). I’m a little afraid of jinxing this, but right now it appears that we’ve found someone really good to do our specialized accounting for $3500, not $8000. If that relationship works out, the math of “a penny saved is a penny earned” means that we netted $21,000 from the fundraiser.

Also, the heating bills haven’t been as high as we feared (so far).

When I wrote all these numbers on the board during class, a student commented, “Some success is still success” and I said, “EXACTLY”. In my experience, that mindset is crucial to being happy (and successful) as a small business owner. When you apply yourself wholeheartedly to a task, even a daunting one, all kinds of indirect benefits tend to show up as a result.2

Also, when your budget is as small as POCA Tech’s, $16,500 is a lot of money, full stop. Which means collectively we raised a lot of money, and we learned a lot too. Thank you to everyone who donated, and everyone at POCA Tech who challenged themselves by engaging in this exercise — whatever the outcome. Once again, we got what we needed.

Yes, I know that regardless of regulation, a lot of acupuncture students have ended up stranded, unfortunately. Someone asked me about recent acupuncture school closures, so here’s a list: Acupuncture Massage College (closed 2024, no notice for students at all); Oregon College of Oriental Medicine (closed 2024, 6 months notice and a teach out with NUNM); AOMA (closed 2024, 6 weeks notice), ACTCM (closure announced 2023, teach out into 2024), MUIH (closure announced 2023, teach out in process), SWAC (closed 2023). A full list of all formerly accredited schools and programs is here.

See also, How to Solve a Problem.