Scrappy

on not giving up

When I was a kid I slept under a patchwork quilt that my great-grandmother made. It wasn’t the kind of quilt that you see on social media under #quilting. The quilt top had no real pattern: It was a random composition of irregular scraps of work clothes, dull blue and gray, thoroughly faded. There were a couple of patches with stripes and one narrow strip of emerald green that looked like an afterthought to try to brighten things up. But it obviously wasn’t made with aesthetics in mind; it was only meant to be used, to serve as an extra layer of warmth. It was made because somebody who couldn’t afford to waste anything (even worn-out work clothes) needed a blanket. It was slowly falling apart after decades of washing and I don’t remember what happened to it, but I’m sure my family didn’t make any effort to save it.

In hindsight, I think that quilt might’ve been a formative influence on my career, such as it is.

Last weekend I had a leadership class with Cohort 10 that ended up with some of us deciding that the subtitle of POCA Tech’s leadership curriculum should be, “how to make things happen when you have no money and no power”. Afterwards I found myself thinking about my great-grandmother’s quilt. A theme of this newsletter, and of community acupuncture (as I understand it, at least) is the idea — the hope — that small, imperfect increments can add up to something significant. Hope itself is something you can assemble out of scraps — provided you have the right mindset.

Doing pain management with patients in the clinic is like this.1 Acupuncture for chronic pain at first might only deliver scraps of relief — an hour, two hours, an afternoon — but if patients and acupunks can keep at it, slowly those scraps accumulate. Stitched together, they start to look like a better quality of life. Sometimes acupuncture by itself isn’t enough, but the incremental relief it offers can give a patient just enough energy to try something else that helps even more. (The list of potential “something else”s is endless: stretching, swimming, massage, chiropractic, a change in medication, a change in doctors, joining a support group, etc.)

Managing chronic illness or chronic pain is a highly individual project, similar to piecing a quilt. Most people have to use trial and error to identify the interventions and strategies that work for them — because nothing works for everybody, and everything works for somebody. That process of figuring out what works, and also what they can sustain, requires patience and persistence. The finished product usually isn’t fancy; it isn’t something meant to be displayed on social media, it just needs to serve the purposes of somebody living their life. It’s private, functional, and always imperfect.

In my experience, one of the fundamental requirements of leadership is to manage your own negativity — as a prerequisite for managing other people’s. This leadership skill comes up in pain management all the time, though it isn’t always obvious to acupuncturists. It’s not the egotistical version of leadership where you’re fantasizing that you’ll single-handedly cure your patient’s longstanding chronic problem — in just a couple of treatments! — and you’re making false promises to that effect. It’s also not about haranguing your patient to change their lifestyle. It doesn’t have much to do with willpower, yours or theirs; it’s looser and more creative than that. In my experience, managing negativity’s about mindset — having a perspective that allows you to hang in with the process long enough for your patient to create that private, functional, imperfect strategy. It’s about how you don’t give up.

Managing negativity is an art and so everybody does it differently2; I’m going to describe how I do it, here goes.

First, and I realize this may be unpopular, is that I don’t give my attention to how things should be. I don’t think about how my patients shouldn’t be in pain, how the healthcare system should have treated them better or how they should be doing something like stretching that they’re not doing. This doesn’t mean I accept the situation or that I’m resigned.

I acknowledge that there’s a version of reality that I’d prefer — but I don’t currently have the preferred version, I have this one. If I want this version to be different, I’m going to have to work with what I’ve got.

What I’ve got are scraps.

This invites the objection of, “But how can you just settle for scraps? You deserve more!” Yes. I agree. But in my experience, some people only ever get scraps, regardless of what they deserve. Nonetheless they manage to make dignity and purpose out of them. If somebody offers me more resources I’ll gladly take them, but if nobody’s offering or if they’re actively refusing, I choose to tap into the long tradition of poor people’s creativity and self-agency.

Political power and economic power aren’t the only kinds of power, and leadership isn’t always about trying to get more of them. (This is news to a lot of acupuncturists.) And before anybody complains that I’m being defeatist, please remember that we’re trying to pass an actual law (HB 2143!) that would give laypeople the power to legally provide 5NP in their communities. We’d never have gotten to the point of having a 5NP Coalition in Oregon, though, if WCA hadn’t spent two decades building a foundation for it, out of scraps. We had nothing when we started, and we’d still have nothing if I’d spent my energy on arguing about how we deserved more.

When we were talking about this in class, one of the students commented that successfully working with scraps requires that you give up any sense of entitlement. That’s another hard one for acupuncturists. It’s true that I have rock-bottom expectations of societal support; on a certain level my outlook is pretty bleak and I wish that were different — but sometimes my rock-bottom expectations line up neatly with current affairs. In which case I’m not dismayed, I’m well-adapted, and I can still make things happen for myself and other people. (See also: cockroaches of acupuncture.) At POCA Tech we teach what we know, so that’s what I’m teaching in leadership classes.

According to Merriam-Webster, “scrappy” can mean “composed of scraps” or “having an aggressive or determined spirit; feisty”. I’m in love with the overlap of those definitions, where a fighting spirit can be expressed by making something good out of scraps. That kind of scrappy is a way of fighting for yourself and even winning — and it doesn’t require anybody else to lose.

Here’s another plug for the article The Heroism of Incremental Care by Atul Gawande, for anybody who hasn’t read it yet.

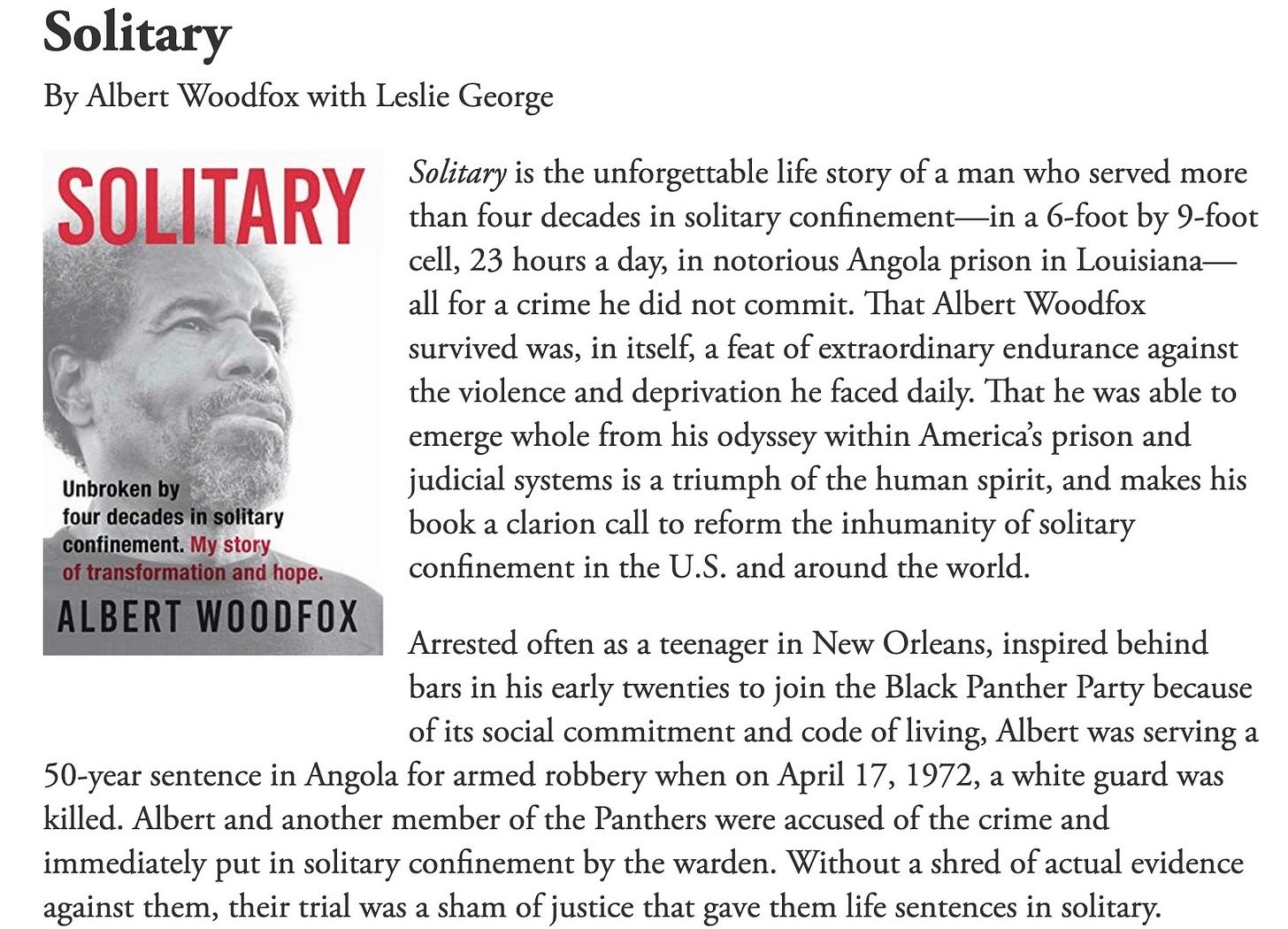

I just finished reading Albert Woodfox’s memoir Solitary, which is a detailed account of exactly what he did to maintain his sanity and his purpose under horrifying conditions — how he didn’t give up. It also provides a valuable perspective on the history and the work of the Black Panther Party. Recommended for POCA Tech students.

Love this article Lisa. Thank you for writing it.

I can barely imagine what "the profession" would be like without the heavy load of entitlement it carries.