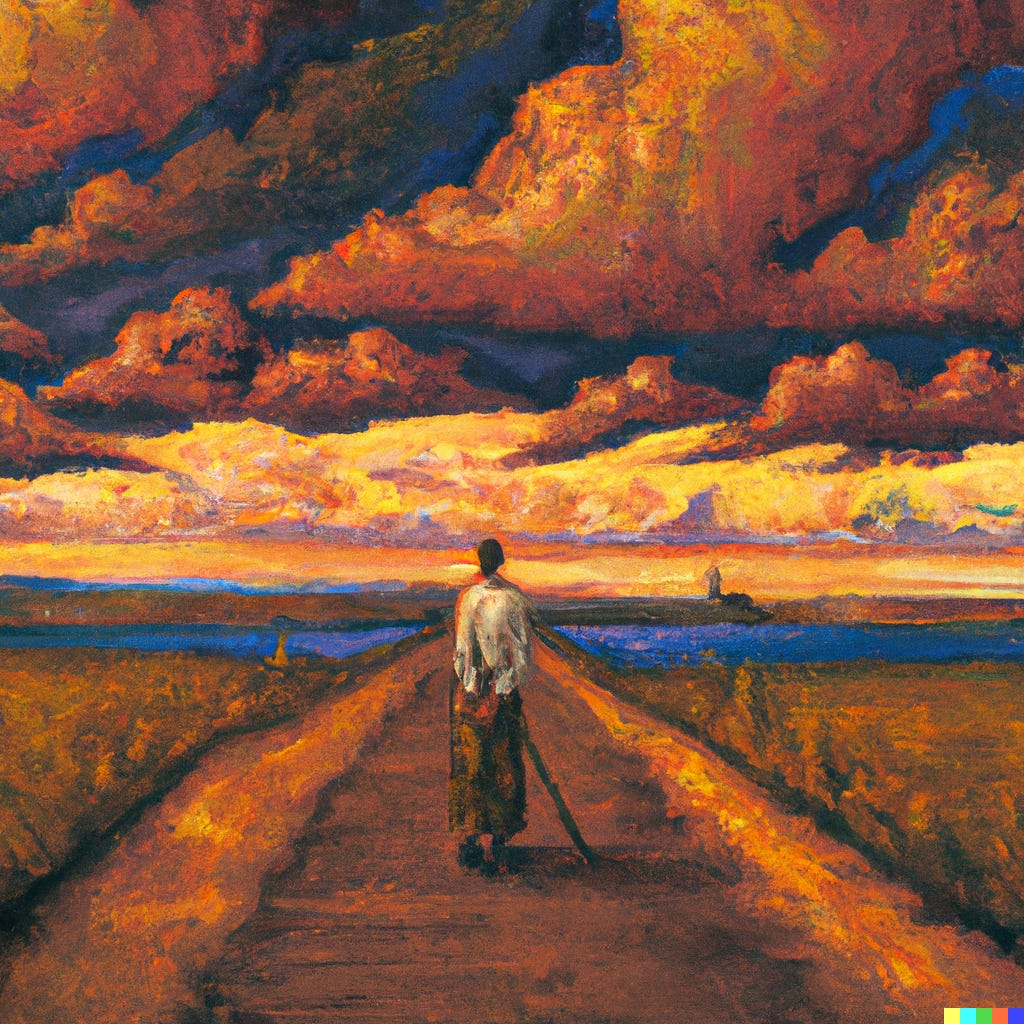

The Road Not Taken: a Small Business Case Study

another post about numbers and the acupuncture profession

Regular readers of this newsletter know that I’m a numbers hound. That’s because it’s hard to distinguish what’s real vs. what’s unreal in the acupuncture profession — but as my friend Whitney likes to say, numbers don’t lie. So when an advertisement for a community acupuncture clinic for sale showed up in my email (“own a lucrative practice in a gorgeous location!”) I was excited to see some numbers that aren’t WCA’s, and excited to talk with POCA Tech students about them.

Back when I started writing this newsletter, I emailed some WCA coworkers and asked what topics they thought we should cover. One responded: Anything that helps people understand WCA. Another said, “Sometimes people seem to feel like there’s a better way of running this business than what we’re doing, whether it’s related to how much we charge, how we schedule, or how we decorate the clinics.” I thought of that sentiment when I looked at the clinic for sale, which opened in 2008 after the owner visited us and took notes on what we were doing.

Their clinic turned out very differently, which makes sense because there are many possible ways to enact the community acupuncture model. Within that flexibility, there are tradeoffs that aren’t necessarily obvious from the outside. So I thought it might be helpful to unpack, in detail, some choices that make WCA what it is — with the other clinic as a sort of case study in what we might’ve been. Also, what can these numbers tell us about the business of acupuncture, and the trajectory of the acupuncture profession?

So without further ado, here are the other clinic’s numbers:

Income: Average gross yearly revenue: $223,249 ($18,604/month)

Expenses: $169,767 yearly ($14,147/month)

Net Profit: Average $53,483 per year ($4,457/month)

4 Licensed Acupuncturists and 1 office manager make up the staff.

One of the L.Acs, the owner, sees patients 1-2 days per week (10 to 12 hours) and takes up to 5 weeks off per year. The clinic as a whole sees on average 110 patients per week; a majority of revenue comes from the part-time employees (60- 70%). It’s open 23.5 hours per week, meaning an average of 4.7 patients per hour (basically half of those hours are filled by the owner). It’s in a neighborhood described as “progressive”, “artsy”, and “renowned for historic architecture and trendy boutiques”.

The clinic has a sliding scale of $35 to $55 per treatment, and by my calculations averages about $39 per treatment.

The business is valued at $91.5K and the asking price is $59.5K. For an acupuncturist to get their practice to a place where it’s been professionally valued as profitable is rare, and a pretty big deal; this clinic is the result of some high-quality entrepreneurship.

It would be easy to assume that if the owner sees patients 10 to 12 hours a week, that means the owner works 10 to 12 hours a week. LOL. No.

Remember there are four employees in this business, which means that the owner is responsible for hiring, firing, training, legal compliance, and troubleshooting, not to mention all the day to day communication that any staff (even a small one) needs. The owner’s also responsible for managing other important relationships, like the landlord; for making sure the bookkeeping and taxes get done; and overseeing the business itself, making big picture decisions. Invisible leadership labor, my least favorite kind! In a small business like this, the owner’s job description will always include everything plus the kitchen sink: everything unfinished that overflows from other people’s jobs, everything undefined or uncertain, every surprise and every curveball.

Knowing the owner, I bet this particular clinic runs like clockwork. But even clocks need maintenance, and the 10 to 12 hours a week of seeing patients doesn’t remotely account for all the tiny calibrations and small acts of care that got the business to where it is — the patience and attention that (on some level) it will always require. Make no mistake, the person who buys this business is buying themselves a job, not a source of passive income. As acupuncture jobs go it’s a good one, at $53K per year with a flexible schedule and abundant time off (assuming, of course, that things continue to go equally well under new ownership) — but it’s still a job with a lot of responsibility and a lot of demands.

When Cohort 9 talked about the “clinic for sale” advertisement in class, all the pros and all the cons, what we landed on was that this would be a great opportunity for the right person (or people). We all hope somebody buys this clinic.

Afterwards it occurred to me that this version of community acupuncture is 1) probably what many acupuncturists imagine and hope their practice will look like after a decade, and 2) pretty close to a best-case scenario. And it’s nothing like WCA’s sprawling, scruffy nonprofit with our 1000 (give or take) treatments per week, 16 employees, $800K yearly acupuncture revenue, wildly elastic sliding scale, plus a volunteer program and a bunch of ever-evolving community partnerships… not to mention a school.

You might wonder: What were we thinking? (Is all that other stuff really necessary?)

Well, one thing we were thinking is that we never wanted to be in the position of trying to sell WCA.

We didn’t become a 501c3 nonprofit because of donations, though we appreciate them tremendously (thank you, donors!) as well as the grants we’ve received (thank you, CareOregon!). WCA runs on the money we make when patients pay for treatments and organizations like CODA pay us to operate a clinic in their facilities. Donations and grants make our shoestring budget more sustainable, but there’s no charitable source of funding that will completely pay for the kind of work WCA does; we have to pay our own way. We became a nonprofit primarily for two reasons: so that we could offer student loan forgiveness (which is a big deal for acupuncturists, thanks again to Oregon Public Broadcasting for pointing that out) — and also, for succession planning.

A fundamental hope of social entrepreneurship is that the interests of business owners and the interest of the community as a whole can overlap so that everybody benefits. That’s also a core concept of the community acupuncture model, the idea that lowering barriers to treatment can create a more stable business for an acupuncturist. And in the case of the clinic that’s for sale, it looks like that’s exactly what’s been happening for the last 16 years. Unfortunately, when it comes to succession planning and individual ownership for a community acupuncture clinic, that’s where the overlap of interests ends. In capitalism, the owner of a business is supposed to cash out at some point.

In the “clinic for sale” advertisement, there’s a detailed list of options for prospective owners. They could make more money by working more hours than the current owner does; they could fire the acupuncturist employees and absorb their patients (which is probably the most cost-effective option); they could transition from an all-cash practice to taking insurance. In short, once they own the clinic, they can change anything and everything about it, regardless of the impact on the community.

And if nobody buys the clinic, when the owner is done with it, it’s gone. If I still owned WCA the way I did back in 2002, that problem would be waiting for us down the road. At some point, we’d be trying to find a buyer and praying that whoever bought it wouldn’t wreck it.

But the thing about a 501c3 nonprofit is that nobody owns it; it’s entrusted to a Board of Directors who oversee it for the benefit of the community. (Hi, WCA BOD members who are reading this! We appreciate you!) It’s not meant to be cashed out ever, and if its internal systems are solid enough and its employees are committed enough, it’s hard for anybody to alter its core identity.

Early on in WCA’s life — back when I did own it — I briefly tried to work with, and swiftly fired, a series of business coaches who insisted that WCA could be very lucrative — if only we would put clinics in nicer neighborhoods, raise our prices, get rid of the red fist logo and the spiky attitude and the quixotic attempts to treat as many people as possible. If only we would refrain from pouring energy into efforts like 5NP, and for the love of God stop giving so much acupuncture away — then everything would be nice and neat, profitable and secure. (Not unlike the clinic that’s for sale.) If only we weren’t so stubborn, we’d be rolling in the clover!1

What this other clinic’s numbers show, however, is that even when you do everything right by normal standards, even when you do all the things that I was urged to do with WCA and didn’t, the business of acupuncture is hard, period. After 16 years, the clinic that’s for sale is still providing 110 treatments per week; it didn’t automatically grow. The owner is still covering about half the hours it’s open. Yes, she’s making pretty good money, but she’s working for it; she’s not rolling in the clover anymore than WCA is.

And that’s because for acupuncturists, there’s no clover to roll in. There’s no guarantee that even if you do everything right, you can cash out at the end. There are only choices and tradeoffs.

At this point, WCA’s choices and tradeoffs are looking pretty good to me. I’m so relieved I don’t have to sell WCA (now or ever), I can’t even tell you. At this point, I mostly get to work on WCA’s business as opposed to in it, which is a dream come true for a small business person. It’s still work, of course, but it’s fun and it’s interesting and my coworkers are great. And yes, WCA’s business is probably way too much by most people’s standards, but being bigger and weirder than a “normal” clinic is what got us through the pandemic and is still — I think — a survival advantage.

Which gets us back to the acupuncture profession.

The clinic that’s for sale is a good business and an asset to its community. But who’s in a position to buy it, when acupuncturists start their careers already owing hundreds of thousands of dollars in student loans? A business that pays its owner $53,000 per year — regardless of all the hard work and goodwill that represents — doesn’t line up with payments on $200K at 8% interest, which is the current rate for federal student loans for graduate school. The acupuncture profession’s debt to income crisis is creating a no-win situation for owners hoping to cash out as well as patients hoping to continue to receive acupuncture.

American culture is individualistic, and the culture of the acupuncture profession here is even more so. It’s taken me awhile to accept that most acupuncturists don’t like to look down the road very far, and most don’t want to look beyond their own immediate self-interest at all. And of course it’s hard for the owners of any small business to find time to think about succession planning. But if you own an acupuncture business in the US (or an acupuncture-adjacent business, of which there are many), and in the back of your mind you’ve been thinking that one day you’ll sell it to an acupuncturist — maybe don’t count on that.

I realize that most people wouldn’t even consider the kind of planning that WCA did a decade ago. Becoming a 501c3 nonprofit and establishing an affordable acupuncture school so that we’d have graduates to hire were really hard to do. They demanded all the resources we had plus some we didn’t; meanwhile plenty of people thought we were overreacting (was all of that really necessary?) It was painful, inconvenient, exhausting.

And it was worth it.

That said, it doesn’t feel particularly satisfying to be right about this. Because now I know what it would take for the acupuncture profession to actually plan for the future: a significant number of people would have to do some inconvenient things that don’t look like they’re absolutely necessary right at this moment. Plus some things that don’t immediately benefit them as individuals. That’s a hard sell.

WCA and POCA Tech are as prepared for the acupocalypse as we can be; at this point I’m less worried about us than I’ve been in a long time, maybe ever. Each year we get better at the business of survival. But a lot of clinics that should continue past their original owners aren’t going to, and a lot of people who’ve been depending on acupuncture will have to figure out how to get along without it.

There was absolutely a trade-off for me between having a business where, as an owner, I could take five weeks off every year versus building something that had a fighting chance to outlive me. The interests of the community don’t always overlap exactly with the interests of the individual. But there’s a point where if you don’t invest in the community enough, there’s nothing left for individuals. It’s hard to predict precisely the moment when the bottom falls out for individuals after years of neglecting the community, but that moment’s coming for the acupuncture profession. Unless enough people are willing to take a different road.

See also: On Selling Out, about community acupuncture’s brush with venture capital and some people who thought WCA and the POCA Cooperative were full of idealists who didn’t understand business. Modern Acupuncture, our capitalist doppelganger, is currently down to 13 franchise locations (from an original 95).

For a second, I thought you were talking about the clinic that I bought (but the numbers don't quite match up). The clinic I bought had 7 acupuncturists and 3 receptionists, pre-pandemic. It was open 7 days a week and doing up to 900 treatments per month. The owner was making $140K per year, working 2 days per week. When I bought it in 2021, there was just one acupuncturist working there (the owner). So, the effect of the pandemic and the coming acupocalypse are starkly on display in my little corner of the Community Acupuncture world. We're back up to about 6 days (9 shifts) per week and around 400 treatments per month. As the owner, I work about 60-70% of all the needling hours and do almost everything else by myself, of course. Anyway, just wanted to chime in that the scenario you described above is completely realistic to my experience. Preach!

As the proprietor of what you would probably call a "boutique practice" my circumstances are different in many ways, and I do feel at a loss when I think about the continuity of my practice. I'm months away from 30 years in practice, and days away from turning 60, and I've got little hope that I'll find someone to serve my clients when I decide to step back - and that's even if I give my practice away. The artist analogy you used in a previous post applies - a different artist could take over my studio space, but would my clients like the art? That may be less of a hurdle for community practices, where clients are more used to a variety of artists. Patients want acupuncture, acupuncturists want to do acupuncture - it should not be so difficult!