Holy moly, last week was a lot.

First, POCA Tech confirmed that we have seventeen students signed up for Cohort 11 and one more in process. So we might have a full cohort of eighteen people (our maximum) AND we had five people defer to Cohort 12! This is the first time in many years that we’ve bumped against our upper limit. Second, we held the first student clinic in our new space and I supervised two brand new interns. The shift was booked solid, plus we had walk-ins, and the interns were absolute STARS. (The new space is magic.)

Also, POCA Tech and WCA had a cameo appearance in the news. Oregon Public Broadcasting published a two-part series: Part 1, With deep debt and low-paying jobs, Portland alternative medicine graduates say their degrees will never pay off (which is mostly about the closure of OCOM, the acupuncture school I went to); and Part 2, Oregon alternative medicine students face a long road to loan forgiveness, which includes an interview with Haley, who’s a longtime WCA acupunk and also a POCA Tech Board member.

Please read those two articles, especially if you’re part of WCA and/or POCA Tech. They’re long and they’re intense, but as Noni put it, they reiterate the point of why we exist.

There have been many times, over the last twenty years, that someone suggested that I was unreasonably upset about the cost and the length of acupuncture education. I insisted that WCA invest in making our own (shorter, drastically cheaper) acupuncture school, even though we didn’t know what we were doing and could barely pull it off. Surely the problem couldn’t be that serious? Did it really require such desperate measures?

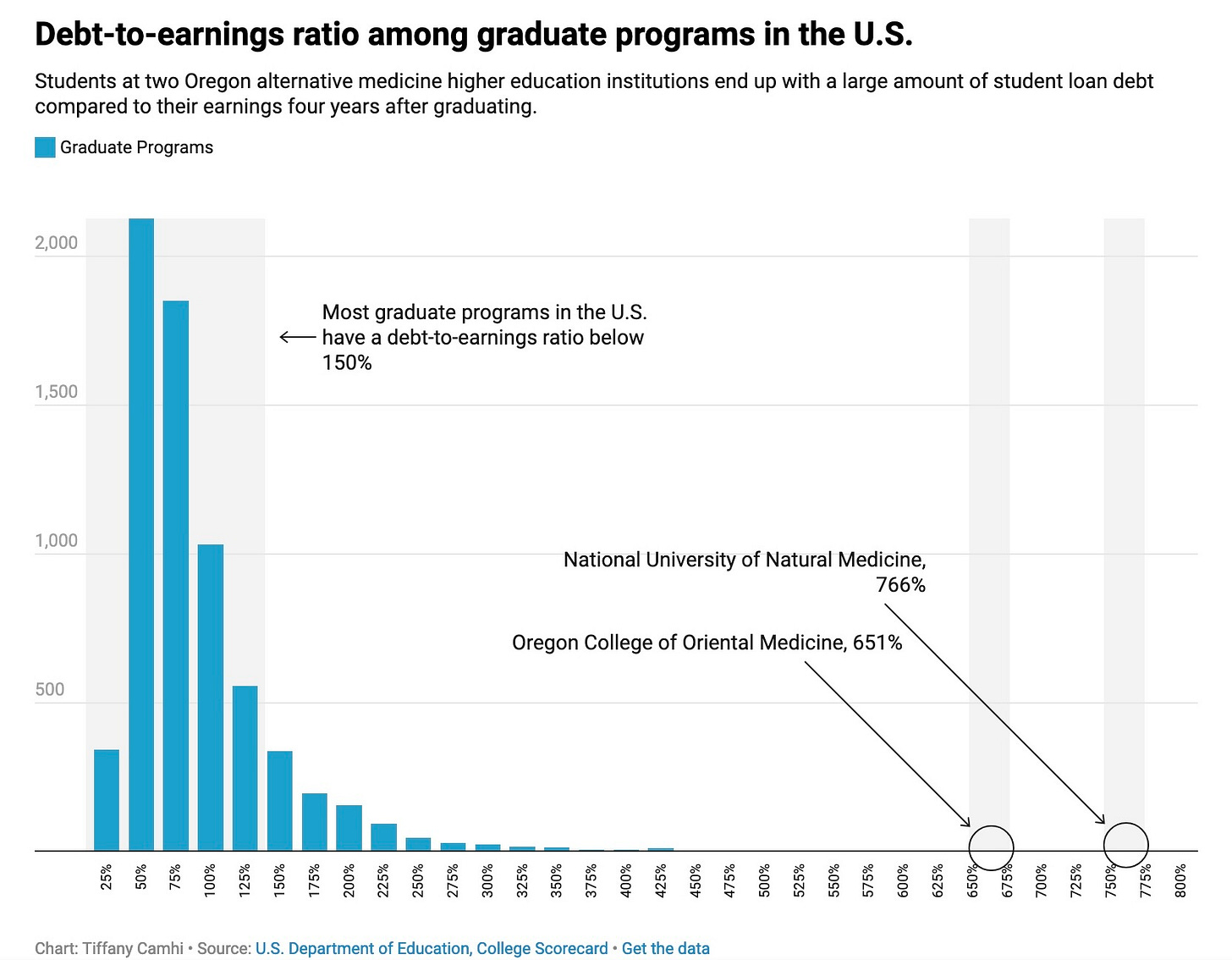

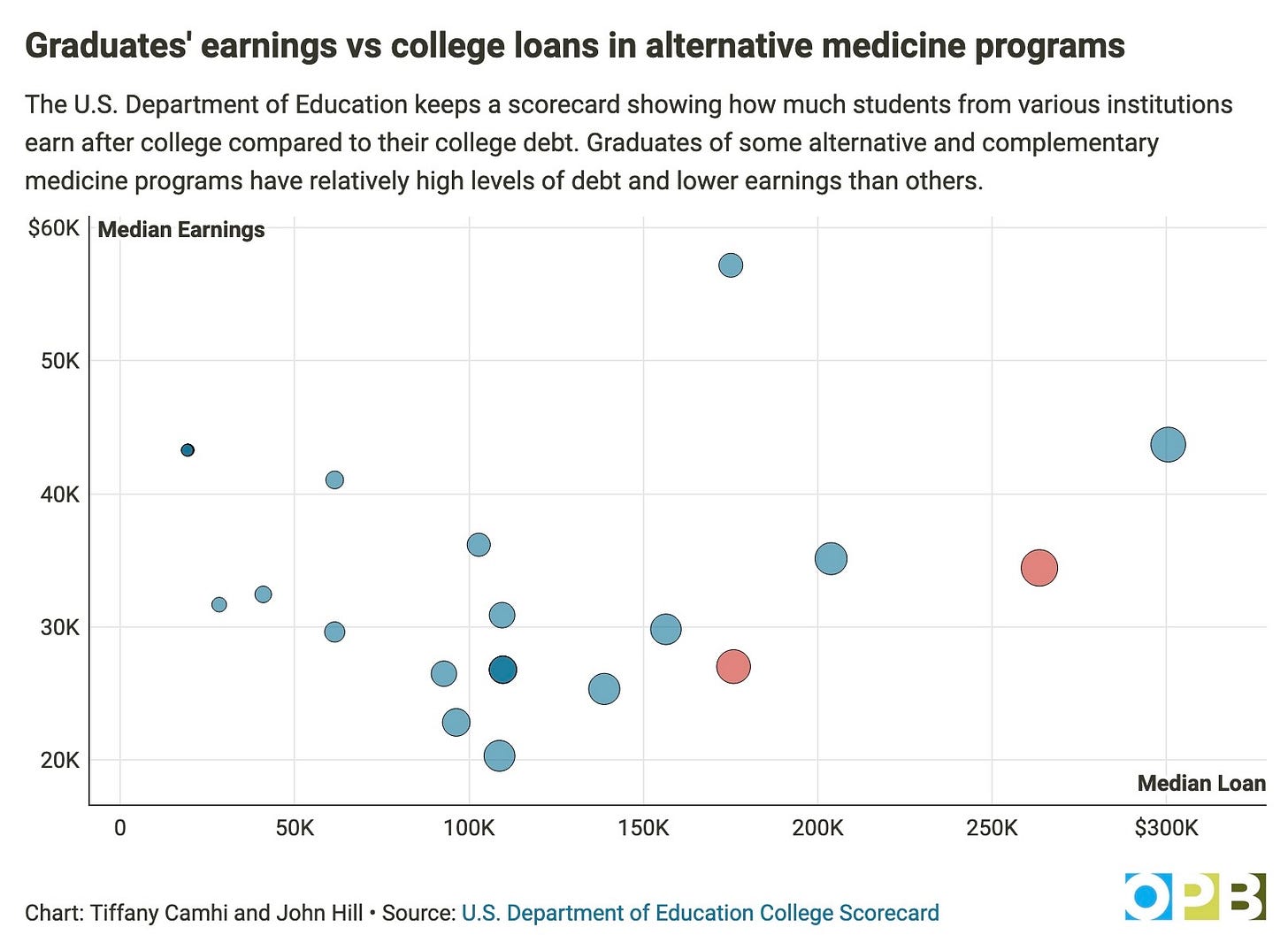

There’s nothing like some high quality, painfully detailed consumer protection journalism to establish that, oh yeah, it’s that serious. Those graphs! Those tables of debt to income ratios for acupuncturists! I imagine those will be shocking to a lot of people.

Another common response to my frustrations was: well, all of higher education is struggling with these issues. It’s not really an acupuncture problem. It’s no worse than every other industry.

But wait, here’s a list of the fifty programs with the highest debt-to-earnings ratios in the country, and — surprisingly even to me — it’s disproportionately stacked with acupuncture schools. Although there are thousands of graduate degree programs out there and less than fifty acupuncture schools. It’s totally worse than other industries!

Honestly, after so many years and so much pushback, this kind of validation is a little disorienting.

As Haley said in her interview: the system is broken.

The articles brought up a whole host of questions, like: Have acupuncture schools been deliberately deceiving people? Who’s accountable for cleaning this up? What’s the solution going forward? I think those all dovetail into the same place, which is the hazardous intersection between the Medical Industrial Complex1 and the Educational Industrial Complex. That intersection’s where the acupuncture profession lives.

This is ultimately about systems, not individuals.2 Not even individual schools. And systems are hard to see, let alone fix.

For years, OCOM’s mission statement was to transform health care. OCOM’s website used to have a banner that said: “This is your medical school. This is where you transform health care.” (So in the first article where a student said they felt misled by OCOM marketing itself as a medical school and OCOM’s CEO responded that “the school markets itself as an acupuncture and Chinese medicine school”? Yeah, that’s disingenuous.) I think that mission statement is an expression of the acupuncture profession’s relationship (not just OCOM’s) to the Medical Industrial Complex — it wants to break in, as Jen observed, but it also wants to change it.

A noble cause, right? Except the Medical Industrial Complex isn’t letting acupuncture in and it doesn’t want to be changed. Nobody in the acupuncture profession — not the schools, not the AHM Coalition, not the state associations — can actually make the Medical Industrial Complex do anything it doesn’t want to do. Laws requiring insurance companies to cover acupuncture as an essential health benefit can’t require them to also reimburse for services at rates that acupuncturists want. And nobody so far can prevent insurance companies from squeezing their margins for every drop of profit, at the expense of providers and patients.

There’s a guiding belief among the leaders of the acupuncture profession that acupuncturists can’t make real money, and the profession won’t be sustainable, without being part of the system. One system that’s easier to get into than the Medical Industrial Complex is the Educational Industrial Complex — where all problems can be solved by longer degrees, more requirements, and higher barriers to entry. OCOM got itself in by the late 1980s, just a few years before I enrolled, and it’s been going deeper and deeper for the last thirty-some years.

A takeaway from the OPB articles is that the acupuncture profession has generally assumed, and allowed students to assume, that being part of the Educational Industrial Complex is somehow transitive to the Medical Industrial Complex. A long, expensive doctoral degree must lead to a well-paid professional job in healthcare, right?

Except it doesn’t.

You know what else happened last week? Oregon’s public academic health center, OHSU, slashed acupuncture from its budget along with all other non-allopathic integrative medicine services. Acupuncturists have been arguing forever that our services save money for the Medical Industrial Complex (which is why they should let us be part of it) but that’s not how the Medical Industrial Complex sees it.

Being part of the Educational Industrial Complex is not, in fact, a key to unlock the Medical Industrial Complex. The people who’ve been paying the price for that collective misunderstanding are the graduates who’ve taken out huge loans. Trying to be part of the system hasn’t made the acupuncture profession sustainable; it’s just caused a lot of students to mortgage their futures.

I don’t think anybody has said it plainly enough: being part of big systems, in our capitalist society, isn’t free. It isn’t a reward that society bestows on you if you’re deserving enough and you jump through enough hoops. It always comes down to somebody paying actual money somehow — and it’s usually way more expensive than it looks. Generally there’s a brutally extractive element somewhere out of sight, like a strip mine leaving wreckage in its wake, that makes it possible to fund the shiny, visible parts.

What the OPB articles revealed is the acupuncture profession’s hidden strip mine. All those graduates with hundreds of thousands of dollars in debt that keeps growing due to compound interest — that’s how we’ve been funding the project of becoming part of the system.

In the second part of the series, the part where POCA Tech shows up, another acupuncturist suggests that the solution to the profession’s problems is to put acupuncture programs in public education institutions, like Portland State.

Before we opened POCA Tech, we tried that strategy. We spent many months in negotiations with PCC’s Central Portland Workforce Training Center, known as CLIMB, because they train healthcare professionals. We really wanted it to work, because we did NOT want to have to make our own freestanding acupuncture school, and the CLIMB Center folks wanted it to work too. But there were too many obstacles. PCC didn’t want to take on a program that had to be approved by a specialty accreditor (ACAHM). However, licensed acupuncturists in Oregon (and most other states) have to graduate from an ACAHM accredited program, so that was a big regulatory barrier.3 Also, the math didn’t work.

We knew we didn’t want a strip mine of our own, we didn’t want the students to mortgage their futures to fund the school, so that meant we needed a program that would cost about $25,000 in total. Because that’s what a lot of acupuncturists earn when they’re right out of school. (Not community acupuncturists, all acupuncturists. Look at OPB’s graphs!) PCC wanted to charge more than that.

Granted, we didn’t approach Portland State about training acupuncturists, but I think the obstacles would’ve been similar — and today they’d be even bigger. No public educational institution is going to want to saddle itself with a program that requires specialty accreditation in a field where enrollment is down and there are almost no jobs — because then they’d be accountable for it, at a time when higher education accountability is a big deal. I can’t imagine any administrator reading those articles and thinking, “Acupuncture education! Now THAT’S what our institution needs to get involved in — sign me up!”

There’s starting to be pressure on the Educational Industrial Complex to mitigate its strip mines (see also: Gainful Employment) so there’s no way anybody’s going to take over ours. (Which happens to be particularly unsightly and embarrassing right now, thanks to OPB’s spotlight.) There’s no tangible incentive for anybody else to clean up this mess.

I was glad that the articles presented POCA Tech in the context of tradeoffs. We actually have a first year class that’s all about tradeoffs, which a student christened the “Why We Can’t Have Nice Things” class. The name stuck, and I’ve had fun teaching it, though now we might have to rename it because our new space is obviously a nice thing. Anyway — spoiler alert for Cohort 11 students — the class is about breaking down in detail what you get, what you give, and what you give up when you provide acupuncture for $25 per treatment as opposed to $100 per treatment. It’s a lively conversation and we cover the whiteboard with lists. And then we do the same inventory for the school itself — what do students get, what do they give, and what do they give up in a school that costs $25,000 instead of upwards of $100,000?

Analyzing tradeoffs is an important competency for small business people. Which almost all acupuncturists are. POCA Tech’s a good opportunity for students to get used to tradeoffs and limits and other realities of small business.

I hope that the OPB articles create an opportunity for acupuncturists to think about the tradeoffs involved in trying to be part of the system. Our cherished conviction that acupuncturists’ role in society is to transform health care, that we have a right to be part of the Medical Industrial Complex and also a right (or a duty?) to change it, is a costly belief to hold. Now we can see who’s been paying for it.

Trauma informed care is the hill I will die on —though thanks to community acupuncture I no longer wish to die on any hills at all, so I hope it doesn’t come up.

POCA Tech has been fully accredited by ACAHM since 2018, though some acupuncturists still refuse to believe it. We chose to offer a master’s level certificate rather than a master’s degree; it’s not a punishment or a sign that we don’t comply with the same accreditation standards as other acupuncture schools.

The reason we chose it is demonstrated by this quote from the first OPB article:

“The student said OCOM marketed itself as a medical school — so they looked into transferring to another school to become a nurse or physician’s assistant. But none of their credits would have transferred. A spokesperson from Oregon Health & Science University said, in theory, OHSU could accept appropriate transfer credits for a bachelor’s or graduate degree but it would not be expected as the curriculum at alternative medicine schools is highly specialized….To find out that years of school credits are basically meaningless anywhere else was really a blow to me,” the student said. “I felt like they lied to me.”

We didn’t want people signing up for our acupuncture school thinking they were getting credits that they could transfer to a more mainstream health care degree. Because that’s not true for any acupuncture school! So we didn’t make a graduate degree at all. Lots of people wondered why we were so stubborn about this; now you know.