On Safety and Boundaries and Murderbot

why community acupuncturists might be cyborgs

First, an announcement from POCA Tech admissions: Noni, our Registrar, will be holding open hours for prospective students on Saturday June 28th 10am-12pm, Wednesday July 23rd 11am-1pm, and Wednesday August 5th 5pm-7pm at the classroom (4636C NE 42nd Ave, at the corner of NE 42nd and NE Wygant). If you’re planning to apply or you have questions about the process, please stop by! Cohort 12 is filling up but there’s still space if you’re interested in attending this fall.

I don’t know about you, but sometimes for me, weeks have themes. Last week’s was safety and boundaries.

Some of this has to do with 5NP — now that we have a law, the next phase is about figuring out how to implement it, which means describing in detail how 5NP practitioners enact safety and boundaries. We talk a lot at POCA Tech about safety and boundaries anyway because we think of them as core aspects of inclusion: You can’t actually include a diverse range of humans in your practice without good, solid structures. Marginalized people in particular have chaos inflicted on them in all kinds of ways; they don’t need more. If all you’re offering is chaos, that’s not really inclusion. To reiterate last week’s post, access to care doesn’t just happen, it requires thoughtful planning.

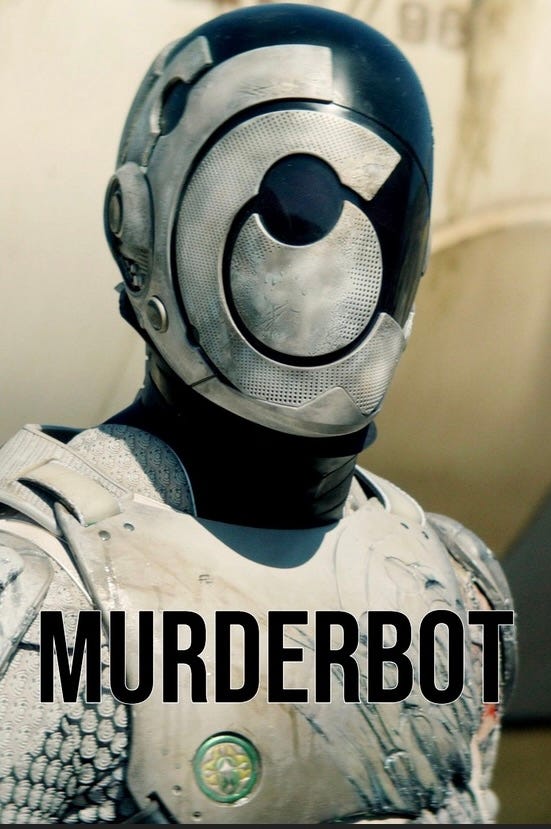

Also, I’m watching Murderbot.

POCA Tech and WCA people know that I’m a big fan of the Murderbot Diaries by Martha Wells (I almost made them required reading) which have now been adapted into an Apple TV series. Alexander Skarsgård isn’t the Murderbot I imagined, but I think he’s a great Murderbot.1 In general the show has some notable differences from the books, but so far they’re interesting and complementary. Anyway, what makes Murderbot so good in any medium is the way that a cyborg mirrors human experience.

"Murderbot is a SecUnit — a partly-organic, mostly-robotic security guard of unspecified gender, owned by The Company and leased out (to human explorers)...There are subtexts to be read into Murderbot — that its experience is a coming-out narrative, that it mirrors the lives of trans people, immigrants, those on the autism spectrum or anyone else who feels the need to hide some essential part of themselves from a population that either threatens or can't possibly understand them...It's the wonder of the character — that something so alien can be so human. That everyone who has ever had to hide in a crowded room, avert their eyes from power, cocoon themselves in media for comfort or lie to survive can relate. It's powerful to see that on the page. It's moving to ride around in the head of something that is so strong and so vulnerable, so murder-y and so frightened, all at the same time."

Awhile back I did some writing for one of POCA Tech’s safety classes about what we call “practitioner persona” and I used Murderbot as an illustration. It seems like it could apply to 5NP practitioners too, so now’s a good time to revisit it. (Or maybe I just want to talk about Murderbot.) Here goes:

I used to think of my practitioner persona as the psychological equivalent of a suit of clothes, like a uniform, that I put on to go to work in the clinic. Now I think of it as a cyborg. Let’s talk about why a community acupuncturist might want to be a cyborg at work.

I wish my own acupuncture school had been a lot more explicit about professional boundaries, and I especially wish that the topic had been uncoupled from shame. I wish I had been guided to approach boundaries as something that I needed to build for myself, not unlike setting up a system for charting or bookkeeping or anything else under the heading of “practice management”. I’ve heard a lot of scolding of practitioners for being unprofessional2, but it seems that not nearly as much energy goes into describing exactly what it means to be professional, particularly for those of us who didn’t grow up in a professional managerial/upper middle class context.

What can be confusing about being a community acupuncturist is how personal and how impersonal you have to be at the very same time. That’s why a cyborg is a helpful metaphor for how to be in the practitioner role: it has both organic and inorganic components and they have to work together seamlessly. Your organic components are about you, your selfhood, while your inorganic components are about your decision to serve your community in a (relatively) selfless way.

The personal, organic components are what make you, YOU. You can’t be a successful community acupuncturist if you’re not yourself. It’s not one of those jobs where a smooth corporate persona will get you far. If you’re doing community acupuncture right, your heart will break repeatedly, in a good not a bad way, but nonetheless in a way that alters you permanently. The personal, organic components of your practitioner persona include your empathy, your kindness, your sense of humor, your likes and dislikes about acupuncture itself,3 and most of all your desire to do this work. The organic components of your practitioner persona will inevitably include some quirks.

The impersonal, inorganic components are what allow you to do the work while protecting you and your patients (from any number of things, including certain aspects of you and your humanness that aren’t a good fit in the clinic). Your inorganic components represent self-discipline, boundaries, routines, order of operations, technical knowledge, and everything else that allows you to show up in a predictable, neutral way for your patients. Which is important because predictability and neutrality are key to trauma informed care.

Your inorganic components are what let you go on autopilot on a packed shift where at least one person tells you something terrible they’re going through and at least one other person does something irritating, like answer their cell phone in the treatment room. Meanwhile you keep a steady pace, giving solid treatments to all your patients one after the other without breaking your stride. You treat everyone the same regardless of how you might feel about them on a personal level. You’re tired at the end of it, but in a good, not a bad way. Your inorganic components steady you.

Part of what we’re trying to do at POCA Tech for students is to install the hardware, the inorganic components, and they’re the same for everybody. (We store them in big boxes in the back room at WCA Cully. Just kidding.) All students learn order of operations, how to do Miriam Lee’s Great 10 in under 5 minutes, how to treat 6 people an hour, how to move around a clinic filled with sleeping people, and how to do an intake. Once the inorganic components are successfully installed, you can count on them to kick in when you walk into a community clinic. No matter what else might be going on in your life, you grab your hand sanitizer, you snag a rolling stool, you open your packet of needles, and you do your thing.

Because your community needs you to do your thing.

What we can’t do at POCA Tech is to manage your personal, organic components, and how to meld them with the hardware — that part is all yours, though we can talk about how we’ve done it for ourselves. That process is unique and everyone has to find their own way through it.

Building a practitioner persona that you can trust to protect yourself and your patients is a way of having proactive rather than reactive boundaries. Your practitioner persona is based on foundational decisions about who you want to be at work, that you’re not going to abandon under stress. That’s a core aspect of safety.

Your personal, organic components may have bias, but your impersonal, inorganic components don’t, and so your practitioner persona shouldn’t either; it should allow you to show up in a remarkably similar way for a dizzying range of people, including people you couldn’t stand if you had to, say, eat lunch with them, as well as people who might be distractingly beautiful or famous. Treating a literal rock star is a good test of your practitioner persona (I’ve treated three, you’d be amazed at who shows up at WCA). So is treating somebody who you suspect has political opinions that are diametrically opposed to yours. (Bonus points if they’re wearing the t-shirt to prove it.) Your inorganic components don’t care about that stuff so they can’t be derailed by it.

Having good boundaries in clinic isn’t just about dealing with situations that potentially cross boundaries, like a patient who yells at the receptionist or asks you out on a date or tries to have a political debate with you (or all three in quick succession; you never know what people might do). I think 90% of having good boundaries is about how you inhabit your practitioner persona on all the ordinary days, in all the ordinary situations. Boundaries that are constructed only for threats and special occasions might not be strong enough for you to respond neutrally when you’re challenged. That’s a big reason we talk about boundaries so much at POCA Tech; our hope is that they become as rote — and as neutral — as opening a pack of needles. Lock and load!

One of the best things about being a cyborg is NOT having to be a perfect human who inspires their patients to try to be perfect humans also. (That’s an expectation that some acupuncturists have, particularly the scholar-physician variety — but trust me, most community acupuncture patients do not want this as a goal, they have more than enough hard things to deal with already, even the rock stars.) You do not have to commit to relentless, perpetual self-improvement in order to be good at your job.4 A cyborg can have wonky human parts that are offset by super-solid hardware.

Ask me how I know.

The corollary though is that you have to give your organic parts what they need, including things they won’t get from the job — or your practitioner persona won’t be strong when you need it to be. Self care is not optional when it comes to maintaining boundaries. In a sense, being a cyborg in clinic means you’re stronger than an ordinary human when you’re at work, but you’re also more limited. Your practitioner persona is only your work self, not your whole self, and you need to attend to your whole self.

Your practitioner persona is who you are when you’re wholly focused on showing up for other people. Outside of that, you still have to show up for yourself as a human with your own quirks and your own needs. You don’t have to improve yourself, but you do have to care for yourself. Because that’s the point of this whole enterprise: humans need care.

On the other hand, Noma Dumezweni is pretty much exactly how I imagined Dr. Mensah and I’m fascinated by how she portrays leadership in the context of a collective. Also I kind of love that the TV writers gave Mensah panic attacks — so relatable.

Maybe you weren’t expecting “the medical equivalent of Green Day” to also be a boundaries nerd? If you call yourself an acupunk, wear a t-shirt to work, and treat dozens of people every day, your boundaries need to be clearer than most acupuncturists’. (Which is kind of a low bar anyway.)

Including your treatment style. If somebody else takes out needles that you put in, they should be able to recognize a treatment of yours the same way they might recognize your handwriting — because it feels like you. Acupuncture shouldn’t actually be performed by robots.

If relentless, perpetual self-improvement is your jam, that’s fine — it’s just important to distinguish it from work. This is an area where POCA Tech diverges from many acupuncturists, and it it’s related to other boundary issues like the question of how much woo/spirituality belongs in your practice and how much personal transformation is something that acupuncture schools should facilitate.