Part One is here and Part Two is here. My friend Tyler Phan Ph.D is an acupuncturist, anthropologist, and all around smart person who’s fun to talk with about controversial topics — like the possible deregulation of acupuncture in the US. (Breathe, everybody, breathe! And read more about Tyler’s work and his ethnography of American Chinese Medicine here.)

Me: Before we get into the controversial topic of the day, can you remind me what kind of anthropology you specialize in?

Tyler: Sure. It’s called material semiotics, and it means the signs and symbols of material things. I look at how things, objects, can determine outcomes of cultures and law and history. I take a science-technology studies approach to American Chinese Medicine.

Material semiotics is a set of tools and sensibilities for exploring how practices in the social world are woven out of threads to form weaves that are simultaneously semiotic (because they are relational, and/or they carry meanings) and material (because they are about the physical stuff caught up and shaped in those relations).

From my perspective it’s the regulation of the acupuncture needle that created our professional/medical culture. The acupuncture profession rests on a special control of the acupuncture needle. No other profession I know of revolves around an object in that way.

There’s a book by Tamara Venit-Shelton, Herbs and Roots: A History of Chinese Doctors in the American Medical Marketplace, that looks at diaspora practices within American Chinese Medicine. Here’s a description:

Historians of American medicine are familiar with the colorful cast of “irregular” doctors who frequented the stage of the nineteenth- and twentieth-century medical marketplace. We know about the Thomsonians, the homeopaths, the osteopaths, and the chiropractors. We know about their bids to compete with Western biomedicine, and the “regular” physicians’ oftentimes aggressive attempt to squash them into obscurity. In Herbs and Roots, Tamara Venit-Shelton turns our attention to Chinese doctors. They were just as embedded in the American medical marketplace as other practitioners of irregular medicine, Venit-Shelton argues, yet they have been overlooked in historical treatments of unorthodox medicine in America. Herbs and Roots is thus a “corrective,” to use Venit-Shelton’s term, which chronicles the 200-year history of traditional Chinese doctors and their therapies in America. The book asks a series of critical questions: How did Chinese medicine arrive in early America? Who did the Chinese doctor treat? What was the relationship between Chinese medicine and Western biomedicine? Why, in other words, was there a market for Chinese medicine in the nineteenth century that persisted in the twentieth century and thrived in the late-twentieth century.

The primary modality of these Chinese doctors was herbs, not needles. And their work was never professionalized. The argument of the book is that these practitioners didn’t have the capacity to professionalize because they were just trying to survive. Professionalization of acupuncture didn’t come into being until white people of the 1960s counterculture got interested. They chose to focus on the needle.

White people + needles = professionalization.

And the thing is, those white pioneers of professionalization did not know what they were doing. They didn’t or couldn’t imagine the consequences of their actions. As a result, some of the ways that the acupuncture profession took shape just don’t make any sense, and you can see that if you look at the acupuncture needle as a sign and a symbol.

They thought of acupuncture as medicine and they wanted to professionalize in the way physicians did, following the template of the AMA. Okay, but medicine is a very complex term, it doesn’t mean just one thing. Medicine is how you practice on bodies.

Me: This is why we need an anthropological perspective, because that nuance is often missing from conversations about acupuncture as medicine.

Tyler: And when you talk about Chinese medicine, do you mean herbs or using a solid filiform needle, which wasn’t introduced in China until the early 20th century? Even the practice of needle retention is a 20th century development. You have to ask, when you say “acupuncture”, what do you mean? How do you define it?

Acupuncturists like to justify acupuncture on the basis that it’s thousands of years old, but what we’re doing now is not thousands of years old. Even Traditional Chinese Medicine as a system only dates to 1958.

Me: Yes. When I think about the kind of acupuncture we do at WCA, these very thin filiform needles that we’re trying to insert as painlessly as possible, followed by a retention time that’s up to the patient — and how one of our goals is for the patient to relax during the treatment, which is often the patient’s goal too — like, some people come to WCA for the express purpose of taking a nap — I’m sure plenty of the acupuncturists of history would be like, What are you doing? You call that acupuncture? Tapping in those tiny little needles and tucking people under your fuzzy blankets? Like it’s all about the snoozing?!? 1

From our perspective we’ve adapted a flexible practice to the needs of the people in our community. We’re providing something that people want, something their bodies respond well to. But I can’t imagine the Yellow Emperor would recognize our interpretation of acupuncture — or for that matter, cosmetic acupuncture or sports acupuncture or any number of other modern interpretations.

Tyler: And it’s not just what is acupuncture, but more importantly WHO is an acupuncturist.

Me: Who’s allowed to touch acupuncture needles. Oh boy, acupuncturists in the US are obsessed with that. It’s part of the project of trying to gatekeep Chinese medicine in ways that don’t make any sense.

As you’ve noted, the filiform needle is a class II medical device with conditions attached to it that even a hypodermic needle doesn’t have.2 And according to Oregon’s acupuncture statute, “Acupuncture” includes the use of electrical, thermal, mechanical or magnetic devices, with or without needles, to stimulate acupuncture points and meridians. So if you touch any acupuncture point or meridian with ANYTHING when you’re in Oregon, you’re practicing medicine and you need an acupuncture license. It’s bananas, and obviously unenforceable if you think about all the people out there who might be innocently massaging, say, LI 4 on their kid who has a headache.

What I want to get into here is how the current regulation of acupuncture —

Tyler: Which is haphazard, with different rules in different states —

Me: How that haphazard regulation actually marginalizes certain practitioners. Because a lot of white acupuncturists don’t think about that.

Tyler: That’s one of the points of my dissertation, that the standardization of acupuncture via TCM and the subsequent regulation via the NCCAOM’s credentialing process, disproportionately marginalizes Asian and Asian American practitioners who come from non-TCM traditions — as well as practitioners that did not come from the American standardization/interpretation of TCM. It’s part of a long history of orientalization and what I call romantic racism.

Me: And as someone who was trained in a family lineage, practiced in hospitals in Vietnam, and still had to take out student loans to go to acupuncture school in the US and pass the NCCAOM exams in order to get a license — you have personal experience of that kind of marginalization.

The possible future deregulation of acupuncture, which could unfold in a totally haphazard way as well — what we’ve been calling the acupocalypse, where the acupuncture profession falls apart because it can’t adapt — that kind of deregulation would marginalize those same practitioners, right? And it could be even worse than what we have now?

Tyler: It could get much worse. As we were talking about last time, medicine in the US is very hierarchical with biomedical physicians at the top. If the existing regulation of acupuncture falls apart without something more equitable to replace it, what will happen is that only the elite biomedical specialists — physicians, osteopaths, doctors of physical therapy — will be able to practice acupuncture. Access to acupuncture will be controlled by the elite biomedical gatekeepers, which will further marginalize — disproportionately marginalize — Asians and Asian Americans who come from a broader tradition of acupuncture.

Me: The story of acupuncture in America is a story about race, class and state power. That’s what I learned from your ethnography, and now I can’t imagine having an acupuncture school without that lens. I don’t think we can understand what’s happening now, the acupocalypse, without actively remembering that history. Without reflecting on race, class and state power.

Tyler: If we don’t focus on building institutions that are grounded in equity, things are going to get bad, quickly.

Me: I was thinking about inclusion and my own experience with making WCA, particularly finding out that some people believe I had some other source of income which allowed me to do this as, I don’t know, a charity project? And how that’s maybe about a sort of American assumption that inclusion is something you consider after you’ve made all the money you want. The idea that inclusion is something extra, some kind of ideological decoration — the cherry on the sundae. But for WCA, inclusion is about making sure enough people can access acupuncture so that we can keep our lights on — so we don’t run out of money. Inclusion is our survival strategy. It’s what gives us resilience. It’s not the cherry on top, it’s the whole sundae, the whole point of WCA’s existence.

In my experience, the acupuncture profession doesn’t seem to care about access or equity or anything like that on an ethical level. But you should care about access and equity on a practical level when you’re running out of money, right?

How about inclusion as a survival strategy for L.Acs?

Tyler: When I was doing my ethnography, the entry-level Master’s degree for acupuncture was already one of the longest Master’s degrees in the country. I interviewed an administrator at OCOM who admitted that enrollment started dropping when they introduced the doctorate. One of the narratives I’ve encountered about acupuncture schools closing is that people think it’s a matter of big schools swallowing smaller schools and I’m like, no — it’s about (formerly) big schools like OCOM and AOMA failing. This is about institutions collapsing under the weight of those degrees.

Me: You and I have been having these conversations for over a decade now and your perspective is that the professionalization of acupuncture according to the template of physicians and the AMA was a mistake —

Tyler: Because it doesn’t make any sense —

Me: And my perspective is, we can’t afford all the exclusivity and the hierarchy — that shit’s expensive and the profession’s going to run out of money — and we’re both like,

Tyler: This isn’t working.

Me:It doesn’t make any sense, we can’t afford it, and it isn’t working.

Tyler: What comes next will either be more equitable — or a complete clusterfuck.

Me: Let’s talk about the possibility of more equitable, and what that could look like, next time.

To be continued

Not to mention all the present day acupuncturists who think that community acupuncture isn’t “real acupuncture”.

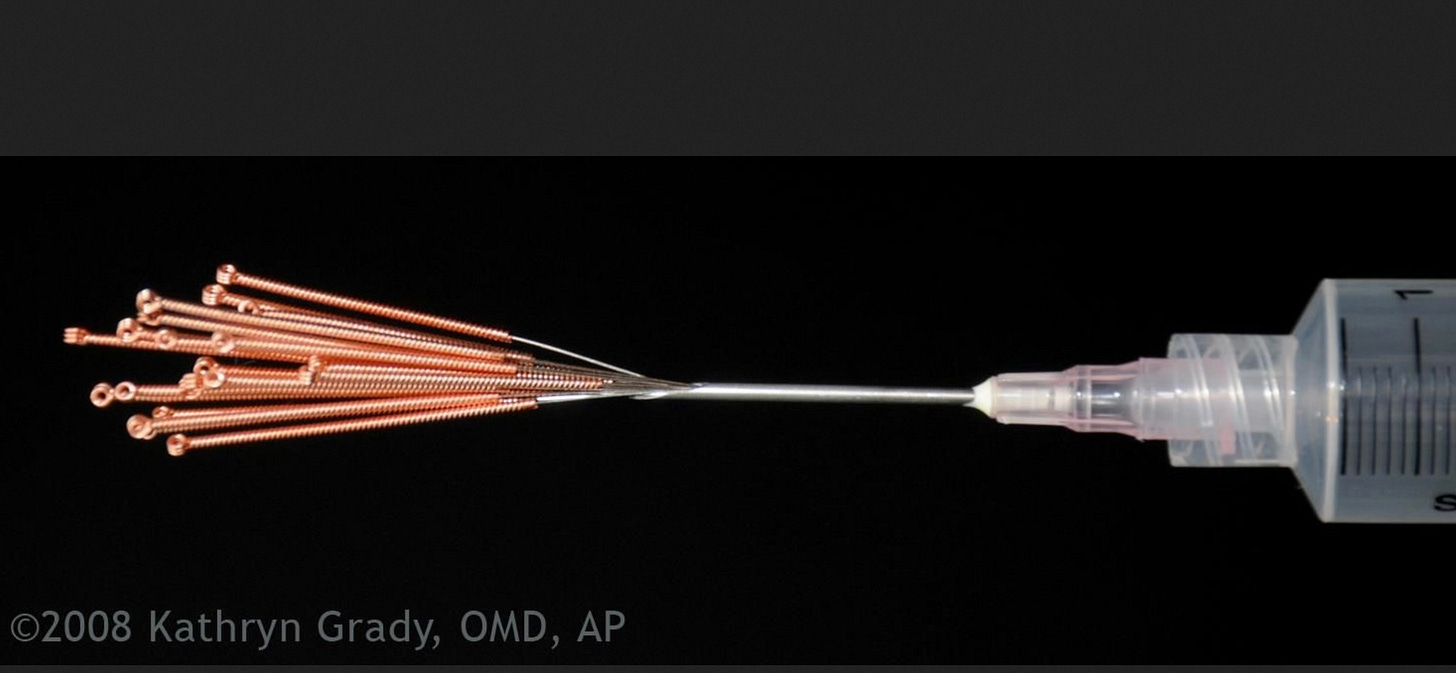

See the FDA’s classification of acupuncture needles with “special controls” vs hypodermic needles without special controls. Acupuncture needles must conform to the requirements for prescription devices set out in 21 CFR 801.109, unlike hypodermic needles. Meanwhile acupuncturists like to compare the respective size of acupuncture vs. hypodermic needles with images like this:

So which is it? Acupuncture needles are no big deal and nobody should be afraid of them, or they’re a HUGE deal and they need to be more regulated than hypodermics?