Part One is here.

We made a technical school for acupuncture because when you hire acupuncturists, you learn quickly that an employee’s skills have a much bigger impact on your business than the grades they got in school. These skills include needling (obviously) but also communication, rapport, time management, and — in a community clinic — overseeing the treatment space itself.

From the moment we realized we had to make a school, we recognized the need to make space for students to practice these skills. Because it was a real headache for employers to retrain people who didn’t have them, and we’d had that particular headache for a long time! Also we knew plenty of acupuncturists who hadn’t acquired the ability to build a patient base for their own small businesses (which didn’t tend to last long) — despite having excellent GPAs. However, it took many more years of actually having a school — like, at least eight years — for us to realize that even the basic skills weren’t enough to help people navigate the gap between graduating and future practice.

What was missing was leadership development. We had to set the expectation for students that they have to practice leadership while they’re in school AND after they graduate. Because you have to lead yourself across the gap; nobody can do it for you. And even students who are talented in clinic don’t necessarily understand that requirement unless it’s spelled out in detail.

Leadership development is now a whole thing at POCA Tech. It’s one of the most significant — and unexpected — ways that the school has evolved. And it’s turned out to be a game changer for us in terms of running the school itself. This makes me wonder about leadership and the acupuncture profession in general, particularly the relationship between leadership (or the lack thereof) to the profession’s existential crisis.

Leadership is such a loaded, complex topic that it’s hard to even know where to start. So let me tell you about where POCA Tech learned to start, before I get into what I think it means. Oddly enough, we start with an article from the 1970s called The Four Stages of Professional Careers, by Gene Dalton, Paul Thompson, and Raymond Price.

Of all the leadership development models in all the books in all the world, why did we pick this one? (Seriously, I had to read so many leadership books before I found it.) Because, like the rest of what POCA Tech teaches, it’s super concrete and it matches our lived experience. The Four Stages model breaks leadership development down into a set of skills that people can learn, practice and get better at, as a result of effort and repetition. Just like every other aspect of community acupuncture, it’s all about identifiable behaviors, relationships and mindset.

Turns out leadership isn’t rocket science, either.

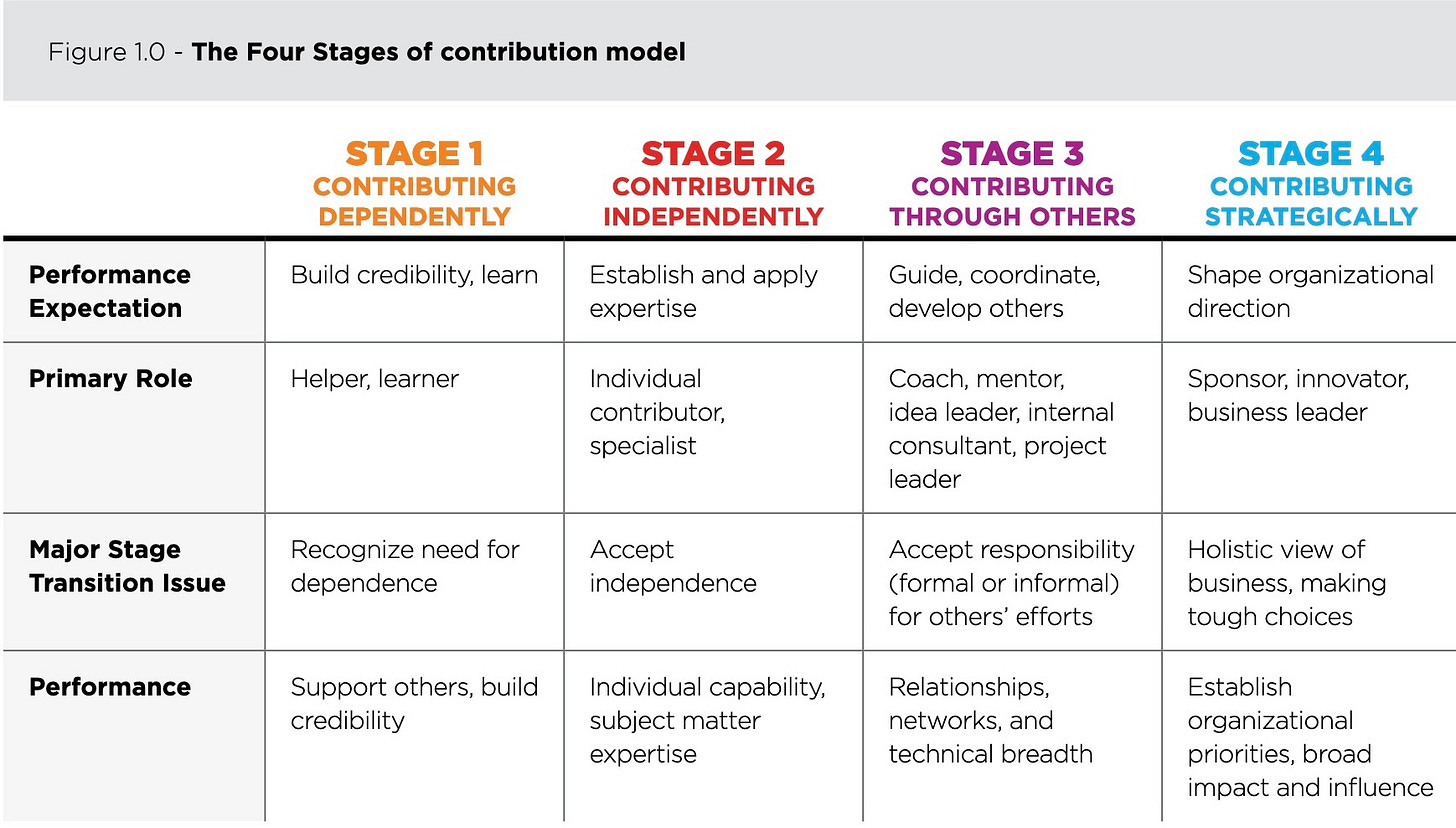

According to Dalton, Thompson and Price, the four successive stages of leadership development are: apprentice (being led), colleague (personal leadership, otherwise known as leading yourself), mentor (local leadership) and finally, sponsor (organizational leadership). Everybody starts out by being led, and everybody goes back to being led when they’re in a new role. Some people never get past the stage of following directions given by others, which is fine — some people don’t want to. The next stage is autonomy within your own job, being able to make contributions independently. Again, some people are content to stay at this stage; many solo entrepreneurs and self-employed people are happy with the independence this stage represents. The third stage is qualitatively different because it involves assuming responsibility for other people and making contributions through them, not just doing your own work. You can’t have an organization without these “local” leaders, because there’d be nobody to coordinate everyone else. Finally, the fourth stage is about using the organization itself as a tool to make a broader impact. Each stage comes with a list of clearly defined tasks and attitudes.

The organizational consulting firm Korn Ferry put its own spin on Dalton, Thompson and Price; they call it the Four Stages of Contribution. I like this diagram:

Being an acupuncture student is all about being in Stage 1: learning, helping, following directions. Becoming an independent health care provider (which is what an entry-level acupuncture program is supposed to do for you) is about progressing to Stage 2. And the absolute minimum requirement for being an entrepreneur is accepting the independence, self-responsibility, and self-leadership of Stage 2. Progressing from one stage to the next requires a conscious decision to move out of your comfort zone into more and more uncertainty. Each stage represents more unknowns and more risk than the stage before. We learned we needed to be much more explicit about this with our students. Our overarching task is to get them at least from Stage 1 to Stage 2.

We try to outline the stages of leadership in neon lights, throughout the program, so that students can identify where they are, where they’re going, and practice the skills to get there. And from the first module of the program, we make it clear that the acupuncture profession has little or nothing to offer to people who can’t get out of Stage 1. If you’re looking for a field with a lot of pre-made structure and opportunities where you can succeed just by doing what you’re told, acupuncture isn’t it!

One of the most self-defeating behaviors of the acupuncture profession is presenting a career in acupuncture as something that students can automatically obtain by earning a degree. Even adding more course hours in practice management to the degree doesn’t address the problem, because a course in practice management is still something you can succeed at by following directions. POCA Tech is a barebones technical school with a pass/fail grading system not just because we don’t have much money, but because we don’t want students to get invested in a nice, neat, prepackaged academic structure that in no way resembles life after graduation.

Because of our shoestring budget, we have a lot of gaps built into the program for students to fill. As I’m writing this, we’re trying to figure out who’s going to hang the posters in our new space. (Spoiler: it’ll be a student!) That’s a very minor example, but that particular task still involves lots of decisions, lots of communication, and a certain degree of managing uncertainty. Each time that students have to step up at POCA Tech to make something happen for themselves and/or the school represents an opportunity to practice the art of making things happen. The art of making things happen in a gap.

If you’re not bored to death with the Four Stages model, here’s a draft of a slideshow that Sara and I are working on about leadership development at WCA through that lens. Because the Four Stages model has also been a gamechanger for running WCA. (Eventually this will be a CEU.)

I was thinking about the acupuncture profession in relationship to the healthcare system, particularly the effort to pass HR 3133 (which still has a zero percent chance of being enacted) as the answer to the profession’s problems. It occurred to me that in so many ways we’re stuck in a Stage 1 mindset. We can’t seem to get past the hope that if we just copy the healthcare system’s template — no matter how dysfunctional that template is — we’ll be rewarded. If we just follow directions, we’ll “build credibility” and upper-middle class professional jobs will just materialize out of nowhere without us having to worry about the pesky economic details or whether there are even enough acupuncturists to handle being included in Medicare. We’re still just trying to get an A on the test. We haven’t yet learned how to lead ourselves.