Just like there are an infinite variety of ways to practice acupuncture, there are probably an infinite variety of ways to organize an acupuncture school1. So why is ours a “technical” school? What does that even mean?

We get this question a lot.

Back in 2006 or so, when we first started putting on workshops about community acupuncture, we made a foundational decision to only teach what we know. To only present what we could back up with personal experience from treating people at WCA, as opposed to offering more abstract ideas. Because there are also an infinite number of ways to do community acupuncture, which you might have observed if you’ve visited more than one community clinic. In our workshops we tried not to speculate about what might work under other circumstances, in other people’s businesses, and only offer what we knew (from experience) worked in our own. If someone happened to ask, “why do you believe that?” we could answer, “well let me tell you about what happened last Tuesday morning…”

And while there’s a certain amount of pure theory that we have to teach at an accredited acupuncture school (see also, ACAHM standards) we’ve doubled down on “teach what we know” at POCA Tech. We want everything we teach to be backed up with our own experience in our own clinics — experience that we hope our students can replicate for themselves, in those same clinics, as soon as possible.

We’re attached to this method in part because a regrettable feature of the acupuncture profession is the degree to which people in it make things up out of thin air and then pass them on as gospel truth.

Maybe this happens in other professions too? I wouldn’t know, I’ve been here pretty much my whole adult life. But acupuncturists seem especially susceptible to dubious methods of filling in the blanks. For example: One of the foundational concepts of community acupuncture is that acupuncture is dose-dependent. The number of treatments that a patient receives over a period of weeks or months has an impact on results — which has important implications for treating chronic conditions.2 When I first wrote about this, many years ago — I think I said something like, “it’s so interesting, now that I have a sliding scale I’m getting much better clinical results, because my patients are coming in frequently and regularly” — I was immediately challenged by an acupuncturist who swore up and down that the idea of dose-dependence was nonsense. Because he was able to cure fibromyalgia with a single treatment, every time! Just one treatment to reverse months or years of chronic pain. When I asked him how he knew his patients were cured with one treatment he said, “They never come back.”

We’re trying really hard not to be that guy. We’re trying not to fill in the gaps of what we don’t know with theories that sound good.

A lot of knowledge about acupuncture is based on anecdotal evidence, there’s no way around that. But you can be concrete, practical, and humble about your anecdotal evidence. You can specify your parameters, as in: patients have reported getting good results from this particular treatment under these particular circumstances. Or: this approach and these systems are what we do in clinic and here’s why; try it out in clinic yourself and see how it goes for you.

That’s what we’ve tried to do, systematically, as long as we’ve been teaching community acupuncture. And the more systematic we got, the more what we taught took on the contours of a very specific job. So it made sense to have a vocational-technical school to train people to do that job.

We made a technical school because we believe that becoming an acupuncturist represents a set of skills that a student can learn, practice and get better at, as a result of effort and repetition. No mystical wisdom required. What is required is self-discipline and self-motivation, plus a willingness to approach acupuncture from a concrete, grounded, and patient-centered perspective.

According to a recent poll, Americans’ confidence in higher education appears to be at an all-time low. Along with that, there’s a new interest in trade schools. As far as I know, we’re the only acupuncture trade school. I wish there were more of us. It would be better for the acupuncture profession if there were more of us, though the acupuncture profession doesn’t think so. See also: (for the most part) professionally qualified.

Another reason that we made a technical school is to address one of the biggest problems in the acupuncture profession: the gap between graduating from school and going into practice. Someone who works for a very established, very respected acupuncture program once told me that less than 30% of their school’s graduates went on to use their degree. Another acupuncture school administrator casually mentioned that it was well-known among acupuncture schools that more than 50% of graduates aren’t in practice after five years.

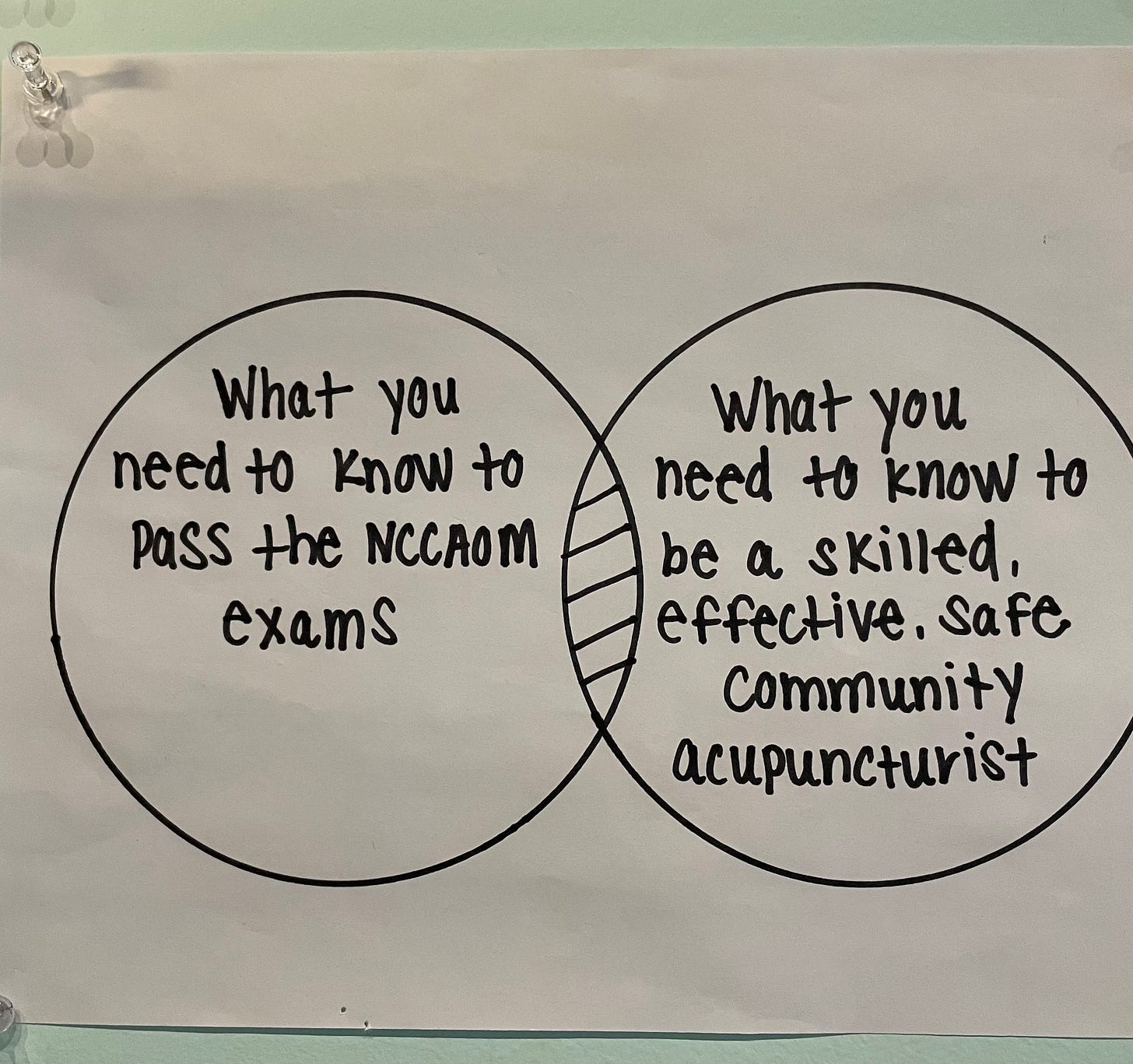

The gap between school and practice could be described as the distance between knowing enough about acupuncture theory to get a credential versus knowing enough about small business and working with people to get a sustainable practice going. (Also the distance between how acupuncture works in books versus how it works in regular humans, which is a topic for a future post.) Some graduates can leap the gap, figure it all out, and build a successful practice. But a lot of them can’t, no matter how smart and motivated they are, and so they tumble head over heels into the void. That void gets bigger with every loan-burdened graduate it swallows. It’s probably going to swallow the acupuncture profession itself, if nobody does anything about it.

But so far, nobody who could actually do something about it thinks that the gap is their responsibility.

And maybe it isn’t POCA Tech’s responsibility either, and it’s true that we (like all the other acupuncture schools) don’t control what our students do after they graduate. Those of us who made the school experienced the gap ourselves, though, and we didn’t want to replicate it for others if we could help it. So we think of the gap as a problem that we’re always working on.

The main way we do that is to continually try to identify and break down the crucial skills that undergird a successful practice. We try to separate them out into small, digestible bits, and then provide as many guided opportunities for students to practice those bits as we possibly can. (See also: pop-up clinics.) It’s not enough to present concepts in class and follow up with a multiple choice test — students have to actually do the thing (or try). Not all the crucial skills are fun to practice (for example, managing uncertainty) but our hope is that familiarity and repetition create a sort of bridge from school to our graduates’ future small businesses. We want school to feel as much like life after school as possible.

Awhile back, one of our Cohort 6 grads, Kerri Quinlan, wrote a lovely testimonial that describes what we’re aiming for:

I’m glad I invested my time, energy and resources into POCA Tech’s program because it gave me the comprehensive framework, and embodied experience, that allowed me to feel like a competent community acupuncturist the day I opened my clinic. My community is already benefiting from being able to access affordable acupuncture in our rural, mountain region, where healthcare options are limited… When I roll up to a patient on my stool I feel like we are partners in their journey toward better health. POCA Tech held the space for me to learn how to be a knowledgeable practitioner, and a partner in someone’s journey. I feel like I have so many tools and insights from POCA Tech’s leaders and instructors that I could immediately apply in my own clinic. As I said to another former student after my first clinic day, “This is almost too easy! We were trained so well!”3

Acupuncture isn’t rocket science.

Being honest about that doesn’t diminish its value. And that’s why we’re a technical school.

Provided you comply with ACAHM standards

Backed up by the GERAC trials

Yes, we do realize that a lot of the acupuncture profession feels that community acupuncture is indeed too easy (in a bad way) and the very existence of a technical school is a blight on the professional landscape. But we’d much prefer for our graduates to feel like their first day on the job was too easy, as opposed to too hard.