Over the past year I’ve written a lot of posts (many more than I planned to!) about the existential crisis of the acupuncture profession in the US. (For example: cockroaches of acupuncture, debt to income ratios.) To all our non-acupuncturist readers: thank you for your patience. Despite all those posts, the whole idea of the acupocalypse can still seem pretty abstract — so I thought it might help if we kicked around some numbers.

Let’s start with Oregon, which is a good state to start with because we’ve been licensing acupuncturists since 1973. We were one of the first states to do so. And we’ve had acupuncture training programs for a long time: OCOM was established in 1983 and NUNM has been training acupuncturists since the mid 1990s. Many of those graduates have established practices in Oregon. Also, luckily for us, our acupuncture licensing body, the Oregon Medical Board, is well-organized and willing to share information. (This isn’t true of all states.) So how’s the acupuncture profession doing, compared to other professions in Oregon?

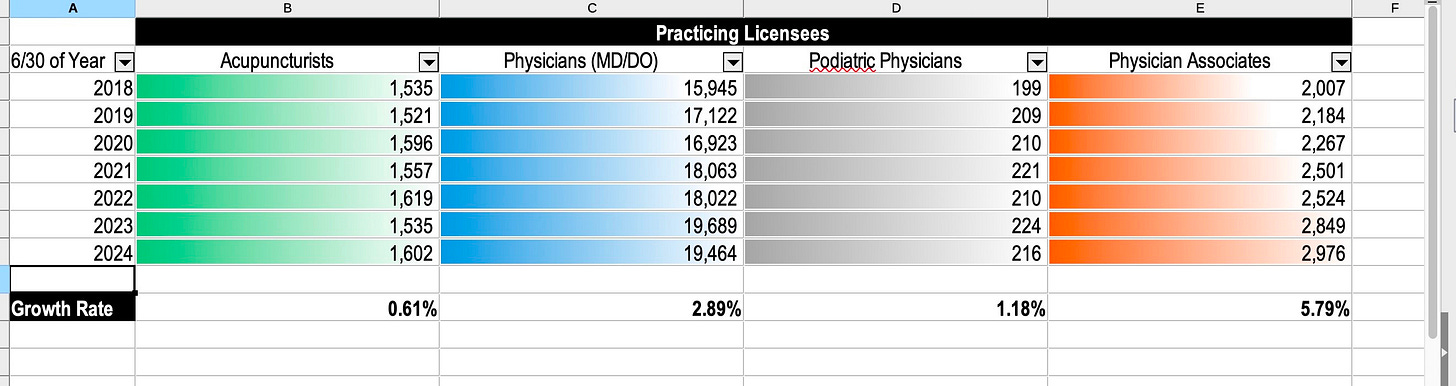

I’m sorry I couldn’t figure out how to make this table (which was provided by the OMB) any larger in this post. I hope you can get the gist: since 2018, the acupuncture profession hasn’t really grown in Oregon, while the other three professions regulated by the OMB have.

This is despite having three local schools turning out graduates every year. Even with declining enrollment, right up until the end OCOM was graduating classes of more than 30 future acupuncturists. Meanwhile NUNM was graduating on average somewhere between 20 and 30 and weird little POCA Tech was graduating an average of 10. Not everybody stays in Oregon, of course, but you’d assume that people who plan to practice in Oregon would go to one of the three Oregon schools if they could.

According to the OMB, almost all professions show some attrition over time, which shows up in biennial license renewals. About 8-9% of licensees don’t renew for a variety of reasons (retirement, moving out of state, career change, etc.).

Some back-of-the-napkin math suggests that every year, the acupuncture profession in Oregon loses about 4% of its members. 4% of 1600 is 64 licensees. That would make sense, if the three schools were graduating 75 or so future acupuncturists each year, and some acupuncturists also come from out of state, that the growth rate would basically be flat. Having three schools in Oregon allowed us to fill in the losses.

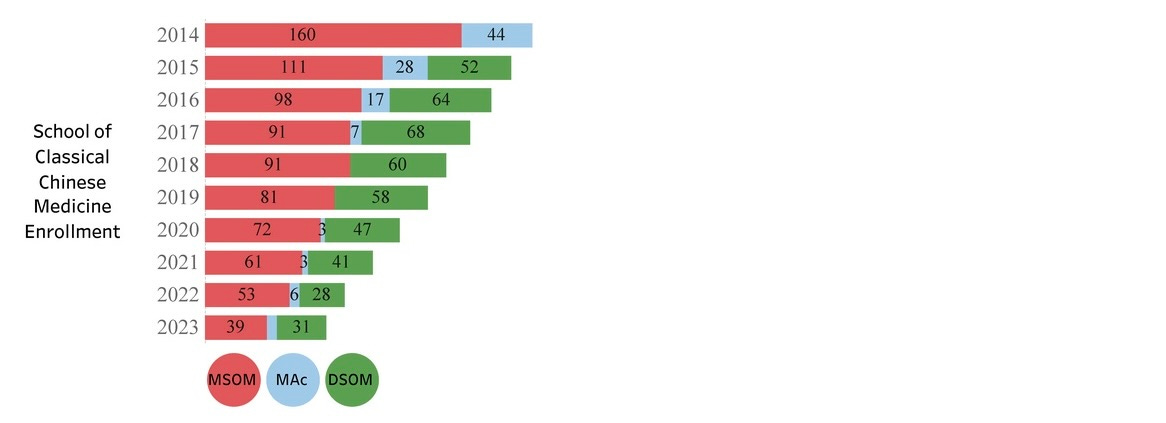

But now OCOM is gone. And take a look at NUNM’s enrollment numbers:

I feel like POCA Tech is doing really well these days but I have to tell you, we can’t make up the difference in acupuncturist production for Oregon. Our goal is to graduate 15 people per year instead of 10, but we can’t get much bigger than that. It’s not just about our classroom space, it’s about being able to provide enough intern clinic shifts for students. (Speaking of which, if any acupuncturists reading this have 5 years’ experience, we’re looking for clinical supervisors! We’ll train you! The pay is terrible but the students are great! Send me a resume if you’re game.)

Let’s apply that 4% per year attrition rate to the acupuncture profession nationally, and compare it to what we know about people entering the profession.

This article by Arthur Yin Fan et al estimates that there were 33,364 licensed acupuncturists in the US in 2023. 4% of that suggests an attrition rate of 1335 acupuncturists per year. In order to grow, we’d need significantly more than 1335 people getting licensed every year.

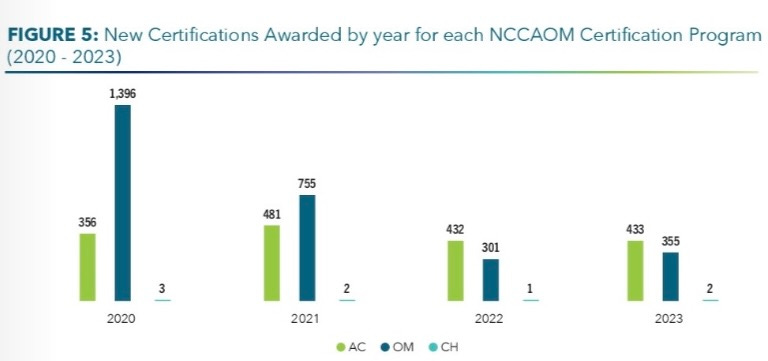

The NCCAOM just put out its 2023 annual report. If I’m reading it correctly, on page 23 it shows that in 2023, the NCCAOM issued 433 certifications in acupuncture and 355 in OM. (As well as 2 in Chinese Herbs, but I’m not counting those because I don’t think they represent two individuals entering the profession; a certification in Chinese Herbs alone won’t get you a license anywhere.) So 788 new candidates for state licensure (since most states other than California require the NCCAOM). 2022 looks similar, with 734 new certifications in acupuncture and OM.

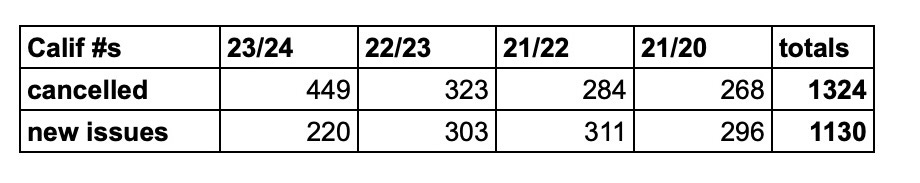

Well, how about California? Here are numbers for the last four years of California license numbers, current through June 2024, courtesy of Whitney Thorniley of POCA:

Again with the back-of-the-napkin math, I think we’re looking at about 1,000 people entering the acupuncture profession nationally in 2022 and 2023. Compared with 1300 leaving it. California’s most recent numbers look particularly grim. (The Yin Fan article calculates a 39% drop in California L.Acs in the last five years.)

In 2024 so far, one acupuncture school closed with six months’ notice, one closed with six weeks’ notice, and one closed with no notice at all. I don’t think I’m allowed to share here what I know about enrollment numbers for ACAHM accredited schools, so you’ll have to take my word for it; we weren’t in a position to turn out more than 1335 new potential acupuncturists even before this recent wave of closures. Not everybody who’s enrolled graduates, and not everybody who graduates gets licensed.

The original vision, back in the 1980s, was that acupuncture in the US would be a profession that looked like, and even competed with, other professions. The comparison table from the Oregon Medical Board is one small snapshot of how that’s not happening. The absolute best case scenario is that from here on out, the acupuncture profession as we know it slowly shrinks like a leaky tire over the next twenty years.

The worst case scenario is that the organizations that make up the infrastructure of the acupuncture profession, specifically the NCCAOM and ACAHM, run out of money too fast to make transition plans (or just refuse to make transition plans regardless), and so in most states, the regulatory structure for L.Acs becomes unworkable. That’s less like a leaky tire and more like having a tire blow out while you’re driving on the highway. In 2022 the executive director of the NCCAOM commented, on the occasion of the NCCAOM’s 40th anniversary, that the organization very well might not have a 45th. She later walked it back and said she was speaking “metaphorically” — but I’ve been worried ever since. If the NCCAOM did run out of money, would it give us six months’ notice, six weeks notice, or none at all?

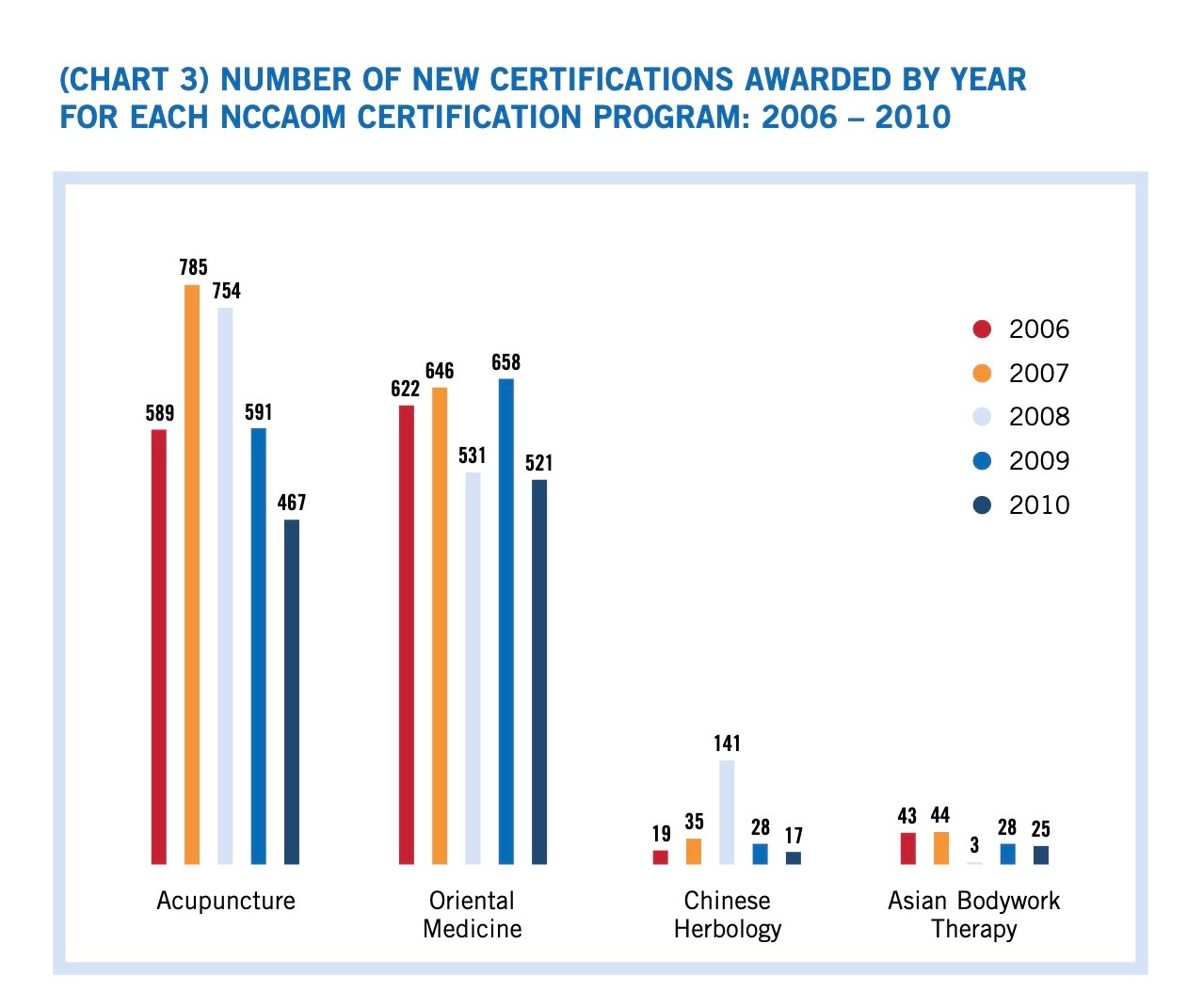

On impulse, I dug back into the NCCAOM’s 2010 annual report to see what certifications looked like two decades ago. They looked better than they do now:

vs.

It seems like our tire’s been leaky for awhile. See also, the California statistics from the same era. These numbers suggest that in the 2000s, there were more like 1800 people entering the profession every year. (Clearly a lot of them didn’t stick around, or we’d have more than 33,000 L.Acs now.) Acupuncturists like to describe acupuncture as “a growing profession” but it isn’t. We should probably 1) stop saying that and 2) plan accordingly.

A quick and dirty summary is that the acupuncture profession was dreamed up in the 1980s, expanded rapidly in the 1990s (due to access to federal student loans), appeared to grow in the 2000s, started showing signs of trouble in the teens, and now, in the twenties, is in crisis. Our regulatory and educational infrastructure was built for a 1980s dream that just hasn’t panned out in the present day. And that’s a problem for those of us who are here now, looking toward our future.

On Thursday, October 24, the NCCAOM is hosting another town hall, promising “a frank discussion on securing the future of Acupuncture in the US.” I’m curious about what they have to say. I think it’s important to recognize that acupuncture in the US and the acupuncture profession in the US aren’t identical (though obviously they’re related). Unless the acupuncture profession can deal with its numbers problem1, it’s time to start thinking about what acupuncture will look like in the future without our current version. A profession that looks like — and competes with — other professions isn’t the only way.

Sorry, HR 3133 still has a zero percent chance of being enacted, so it still doesn’t count as “dealing with the problem”.