Manifesting Community

all about protocols, with a side order of controversy and tomato sauce

One of the fun things about writing this newsletter is the wide range of people who engage with it. Which is also one of the fun things about community acupuncture itself: people who would never cross paths under other circumstances falling asleep next to each other in the treatment room, sometimes even synchronizing their naps. Anyway, among our readers we have acupuncture students, acupuncturists, community acupuncture patients, WCA/POCA Tech volunteers and donors, other Portland community members, and many many people in the category of “I don’t know how you found us but I’m glad you’re here!”

This means that sometimes it’s useful to revisit some basic concepts -- not just for new subscribers, or for new acupuncture students, but for me. I always learn something when I try to put any acupuncture-related ideas into plain language.

So let’s talk about acupuncture protocols! I’m very excited about the whole 5NP in Oregon thing but I know there are plenty of people who are like, wait what? Five Needle Protocol — what even is a needle protocol?

Ah, welcome to a controversial topic.

A protocol is a pre-determined set of acupuncture points. 5NP is five specific points in the ear. Miriam Lee’s Great Ten (ML 10) is five specific body points, two on the legs and three on the arms. When we say 5NP, we always mean the same points: Lung, Liver, Kidney, Sympathetic, and Shen Men. When we say ML 10, we always mean Spleen 6, Stomach 36, Lung 7, plus Large Intestine 4 and 11.

So far so good?

A protocol sometimes represents a decision that’s been made about how to deliver an acupuncture treatment before a patient walks into the clinic. 5NP, for example, was developed as a strategy to treat substance use disorder, stress and trauma. Everybody who shows up for a 5NP clinic gets a 5NP treatment, based on the assumption that they’re there to work on substance use disorder, stress and/or trauma. On the other hand, Miriam Lee developed ML 10 not because she expected all her patients to come to her clinic for the same reasons, but because she was confident that ML 10 would get good clinical results no matter what her patients came in with.

5NP and ML 10 both represent many years of clinical experience distilled down into a handful of acupuncture points. The activists of Lincoln Acupuncture Detox Collective in the 1970s developed 5NP by delivering thousands of treatments; they tried different auricular acupuncture strategies and eventually they landed on those particular points. Miriam Lee had decades of clinical experience with acupuncture before she started treating 17 patients an hour in Palo Alto. In her book Insights of a Senior Acupuncturist, she compares the demands of treating so many people to an olive oil press -- without the pressure, you don’t get any oil out of the olive. In her case the oil wasn’t just the protocol itself but the sheer clinical creativity that she discovered under challenging circumstances.

Speaking of food, an acupuncture protocol is not unlike a recipe. A good analogy for 5NP or ML 10 is Marcella Hazan’s legendary tomato sauce, whose “radical simplicity still has the power to shock,” according to Epicurious. It requires only canned tomatoes, butter, salt, and an onion which you take out before serving. Only four ingredients, but volumes have been written on its excellence. Or as one food blogger put it, “When it comes to essentials, like tomato sauce, originality is overrated.” Marcella Hazan didn’t create a four ingredient recipe that requires almost no cooking skill because she didn’t know what she was doing in the kitchen, but because she really, really did.

Sometimes a protocol represents a decision that an acupuncturist makes after they check in with a patient. One of the most important skillsets we want to teach at POCA Tech is what’s known as clinical judgement, which contains a hefty percentage of intuition. Sometimes there’s a direct line between your intuition and a set of points you know intimately because you’ve practiced them a lot. Protocols will speak to you.

Every community acupuncturist I know can describe the experience of rolling up to a patient and feeling every bone in their body vibrate with “ML 10.” Do Miriam Lee’s Great Ten, their clinical judgement is telling them, because that’s what this person needs today. Maybe you had other ideas about their treatment; let those go. Same for 5NP; maybe you weren’t planning to do ear needles at all but intuition told you to add them. Sometimes you just know, though you can’t say how you know. The more treatments you give, the more often this knowing shows up to help you, and protocols are often part of it.

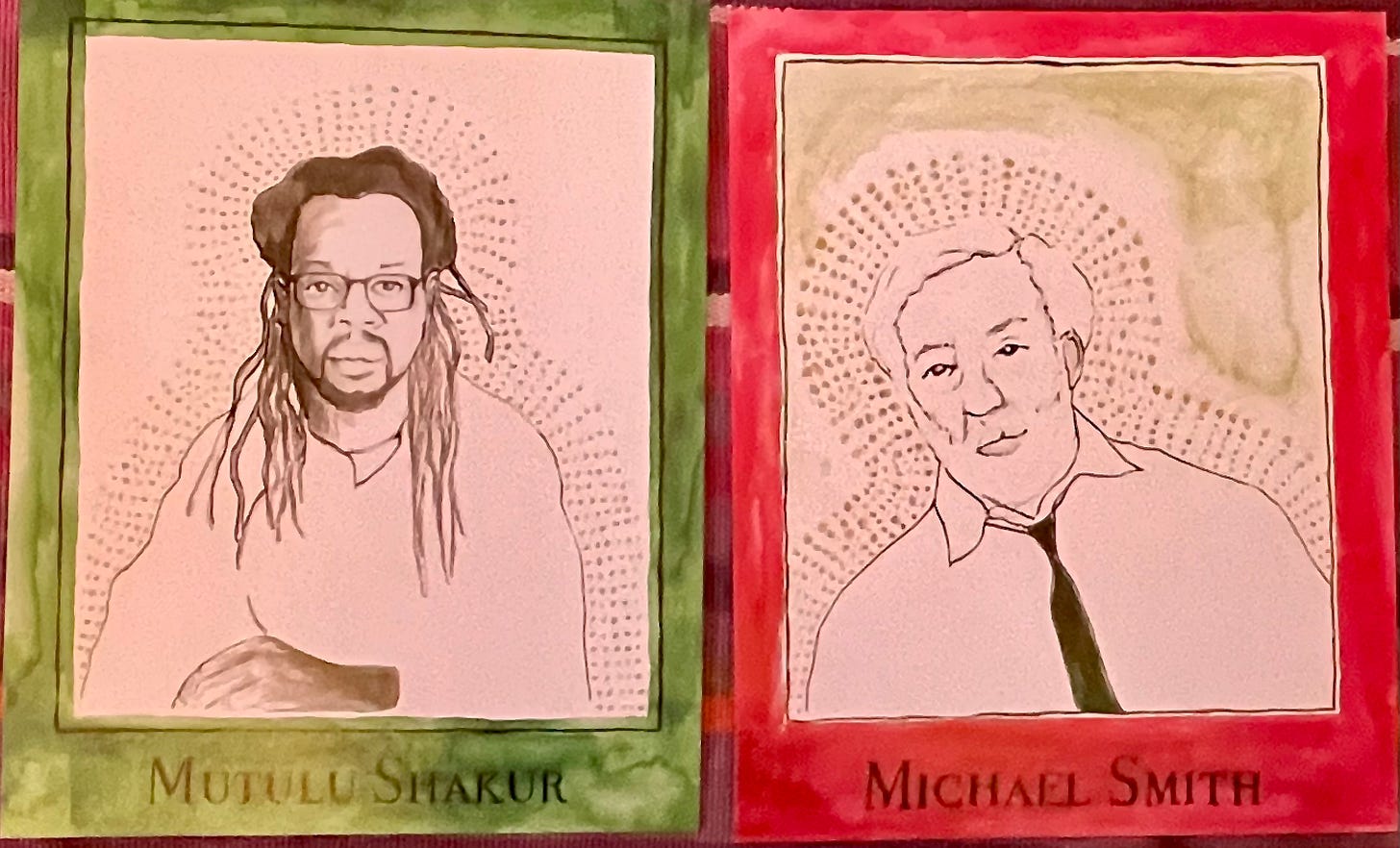

A recipe can be a vehicle for transmitting cultural heritage, identity and wisdom (see also: “foodways”). Similarly, an acupuncture protocol is a way of handing down the skill, experience and spirit of our clinical elders. A protocol is a gift from the past; it represents survival, resilience, devotion. A protocol is a manifestation of community across generations. Needling 5NP or ML 10 in the clinic is like a ritual that invokes the courage and compassion of healers like Mutulu Shakur, Michael Smith, and Miriam Lee.

It’s an honor to get to use their protocols.

Now I almost can’t bring myself to talk about why acupuncture protocols are a controversial topic.

Let’s just say it’s another entry under the heading of acupuncture needs a new narrative. The current narrative about protocols in the acupuncture profession is that they’re a substandard form of acupuncture: “dumbed down” and “cookbook”. This narrative isn’t based on robust research studies showing that protocols are less clinically effective than acupuncture points chosen by other means. (If any such research exists, I’d like to see it; it seems like it would be hard to design and even harder to execute. ) Certainly, there’s value for acupuncturists in knowing how to construct treatments without relying on a protocol (a skill we also teach at POCA Tech) but it’s possible to appreciate that value for itself, without hating on protocols. This isn’t a zero sum game.

Maybe you don’t want to cook a huge batch of Marcella Hazan’s tomato sauce every day for a crowd, or even make it once a month for your family. That’s fine! But saying “no thanks, not for me” is completely different than complaining that Marcella Hazan’s tomato sauce is bad, or bad for people who are hungry.

Lots of people are hungry.

Something we regularly remind POCA Tech students about is the difference between how a practitioner experiences giving a treatment versus the experience a patient has with receiving that same treatment. A good acupuncturist keeps that difference in mind and tries to prioritize the patient’s point of view. I think the controversy about protocols is an instance in which the acupuncture profession as a whole needs a similar shift in perspective — and maybe to entertain the possibility (deep breath) that originality is overrated.