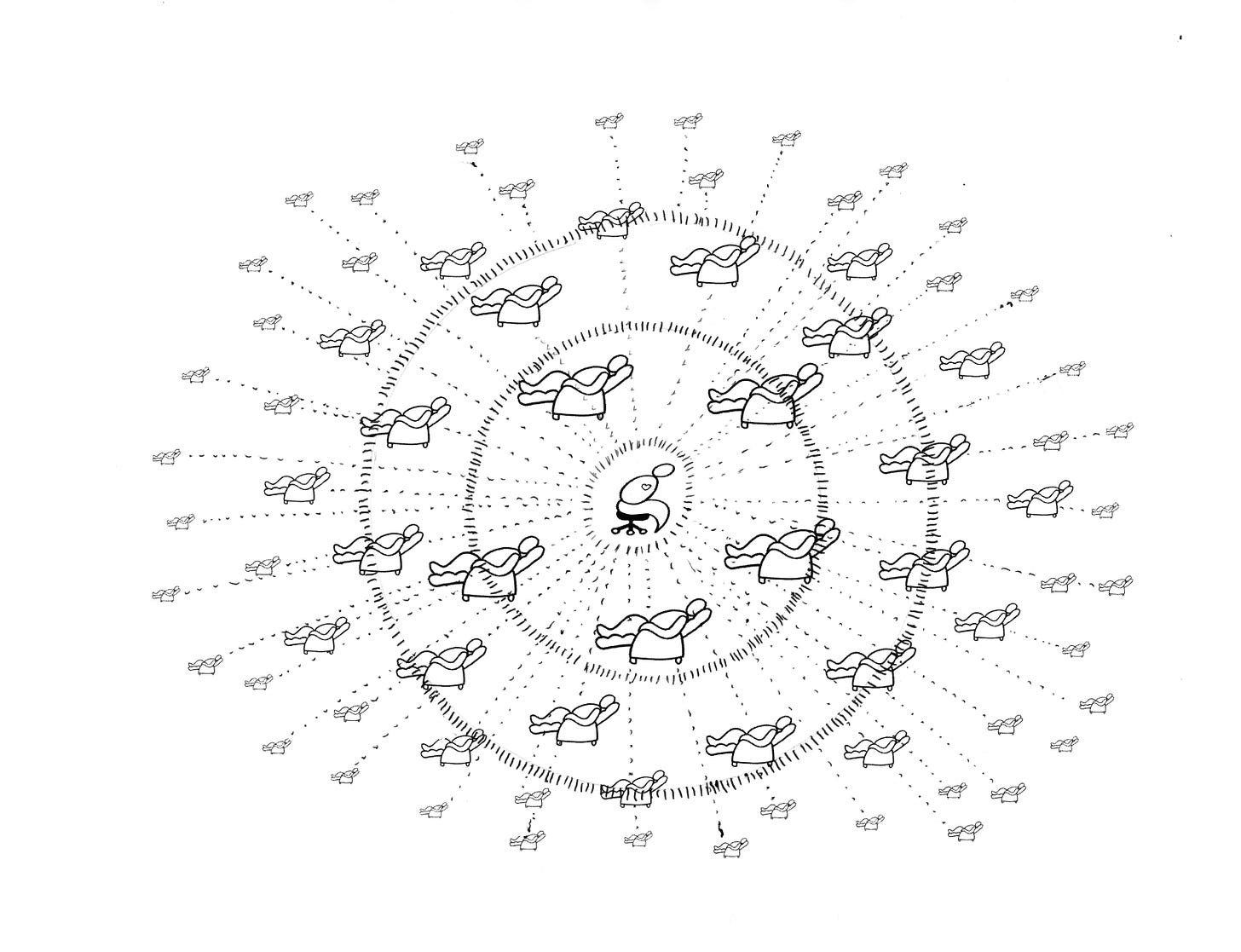

Last week I taught a class for second year POCA Tech students, most of whom have recently started interning in clinic. The class is called “Holding Space” and it uses the diagram below, which represents a community acupuncturist on their rolling stool being a kind of atomic nucleus at the center of a little electron cloud of patients (note the tiny recliners!) The diagram expresses the core of the community acupuncturist’s job: holding space for lots of different people to heal. The diagram also represents the invisible work involved in building a patient base, which every acupuncturist needs to do if they’re going to make a living.

This class is always interesting for me because it’s mostly discussion, so it’s a little different every time depending on what people share. I started out by asking the students, what questions do you have based on your experience in clinic so far?

One student said, I feel like I was prepared for the basics of interacting with patients about what brings them to the clinic, but I’m not sure I know what to do about the conversational space that’s left over, that maybe could be filled with... small talk? Or something? And I was like, how great, we’re jumping right into the deep end! Because the question, what do I say to patients in the available time that I have? is another way of asking, what exactly is an acupuncturist DOING with their patients -- besides putting in needles?

It’s a high-stakes question. It links back to Camille’s presentation about narratives, and also to the argument about whether acupuncture is valuable in itself, or just an odd bit of a larger “complete system of medicine”. In my experience, a lot of acupuncturists struggle to answer the question, what am I doing? The space that opens when you don’t quite know what to say to a patient can fill with all your insecurities and doubts. Besides our second year POCA Tech students, we had two graduates of other acupuncture schools sitting in on the class, which was great because they were able to offer a different (sometimes troubling) perspective about the narratives they had picked up in their educations.

As we talked about the diagram over the course of a couple of hours, what we arrived at was: it’s all about making connections.

A community acupuncturist’s job is to make connections — with lots of different people in lots of different ways.

That’s the central task of building a patient base. And with each individual patient, it’s about facilitating the person’s connection to their own healing process -- to their bodies, to their experiences, and to hope.

One of the non-POCA Tech students shared that in their education, their practice management classes were focused on insurance billing, patient retention, and marketing techniques. Separately, they had classes about an acupuncturist’s professional responsibilities. But nobody ever said explicitly: your practice is made up of relationships, and it’s your job to build those relationships. You need to make the connection with the people who will be your patients -- you can’t expect them to do that for you and you can’t expect it will just happen on its own. Making connections is a specific kind of work that you can get better at with practice. It’s an aspect of both clinical skill and practice management, and also, those aren’t separate!

I said, in my experience a lot of acupuncture schools sort of talk AROUND the central task of building relationships, and some students can sort of work backwards from marketing and patient retention and realize that it all comes down to making connections — but a lot of them can’t, so they’re pretty lost after they graduate. Something else that doesn’t help: the dominant narrative that acupuncture is a growing profession — so all new graduates have to do is to show up with their white coats and their doctoral degrees, and patients will just flock to them, no relationship-building needed!

As Camille said, narratives are deliberately curated to serve specific agendas and the narrative of acupuncture is a growing profession serves the agenda of acupuncture schools, but not so much their graduates. Forgive me, I’m going on a tangent for a minute —

In an article about the history of the acupuncture profession, in the spring 2011 edition of The American Acupuncturist, I came across an acupuncturist headcount — on page 25 it says: “There are now approximately 27,000 licensed practitioners in the U.S.” In a recent article (August 2023) on “Governing Therapeutic Pluralism”, Nadine Ijaz and Heather Carrie estimated the number of licensed acupuncturists in the U.S. to be approximately 28,000. As it turns out, it’s quite difficult to count licensed acupuncturists across 50 states; after corresponding with the authors, they noted that 28,000 might be a typo and the number of L.Acs might be approximately 29,000. The discrepancy points to the challenge — even for academic researchers — of obtaining a firm number from the patchwork of acupuncture regulatory bodies.

The thing is, though, that from 2011 to 2023, accredited acupuncture schools were graduating (I believe) between 1500 and 2000 potential new practitioners per year, assuming that I’m reading the ACAHM data correctly. Circa 2011, there were about 60 acupuncture schools with a combined enrollment of around 8,000 students in a mix of three and four year programs; now there are about 50 with a combined enrollment of around 6,000 students, so divide the total by 4ish to get the annual number of graduates. So whether the total national L.Ac headcount has increased by 1,000 or 2,000, that’s over the course of twelve years, which is barely growing. Something is off.

So the title of this narrative is not “Yay, a Growing Acupuncture Profession!” it’s more like “Why is There a Hole in the L.Ac. Bucket?” Where did all those graduates go?

But let’s get back to what community acupuncturists say to their patients.

This practice is an art, so it’s not like there’s a checklist somewhere of approved topics. Part of becoming a good acupuncturist is learning how to tune into people enough so that you can tell when the best way to make a connection is actually by chatting about the weather or making a joke. In general, though, holding space for patients means bringing a warm and genuine curiosity about how their experience with acupuncture is going for them. Holding space can mean asking questions like, so how’s your sleep? What’s your energy level been like lately? Has anything changed since the last time you were in?

Sometimes new practitioners can get overwhelmed when a patient has a lot going on, which many patients do: multiple chronic conditions, stressful living situations, “complex bio-psycho-social challenges” which is a fancy way of saying that our society makes their lives really hard. In these situations, we teach our interns to ask, “What’s bothering you the most right now?” and then tailor the treatment to that -- because one of the most important services we can provide is to help patients find some relief in the present moment. To be able to relax where they are (which requires their acupuncturist accepting where they are and meeting them there).

That should be a community acupuncturist’s priority, and so in some circumstances, making small talk represents a missed opportunity. Similarly, lots of patients like to ask about what each acupuncture point is for and lots of acupuncturists love to expound (I’m speaking from personal experience, I also loved to expound!) -- but a lecture about acupuncture theory is often not useful because it’s too abstract, too heady, and too removed from what’s most important, which is simply -- how’s the patient feeling right now?

It’s hard to adequately express in words, but holding space means getting into reality, into the present moment, with your patient and supporting them there. Not somewhere else.

It takes intention, focus and practice to get into reality with other people. Many acupuncturists in the U.S. are powerfully drawn to fantasy and if you’re an acupuncturist, you probably need to make a concentrated effort to orient yourself toward what’s actually happening as opposed to professional narratives about what should be happening. Speaking for myself, I had to work to get into reality.

But let’s talk about fractals.

Fractals are self-similar repeating patterns and they have everything to do with community acupuncture. In this case, the pattern of an acupuncturist connecting with an electron cloud of patients repeats at the organizational level, and it’s what WCA is trying to do now: to be an organization making connections with other organizations. Just like for the individual acupuncturist, WCA needs to put intention and effort into the process of building a little cloud of mutually beneficial relationships with other organizations. Also, we couldn’t figure out the relationship building all on our own, we needed coaching and support from Camille.

At the level of the acupuncture profession, we can see how acupuncturists put their energy and their attention into professionalization instead of making connections with communities. They thought professionalization and its trappings (white coats, doctoral degrees, turf warfare) would be a stand-in for relationship building — more status, less effort! — but it wasn’t. Because nothing is a stand-in for relationship building, there’s no substitute. If we want the narrative acupuncture is a growing profession to be true, we need to focus on making connections.