Recently I had a conversation with an acupuncturist who said, “Remember when you were a new graduate, the first time you had a patient who wasn’t anything like the textbooks?” And I said oh yes.

Almost none of my patients have been anything like the textbooks, that’s how we ended up with WCA! This represented yet another problem when we opened our own acupuncture school: We’d had decades of experience that didn’t match the way that acupuncture is taught and learned in US acupuncture colleges.

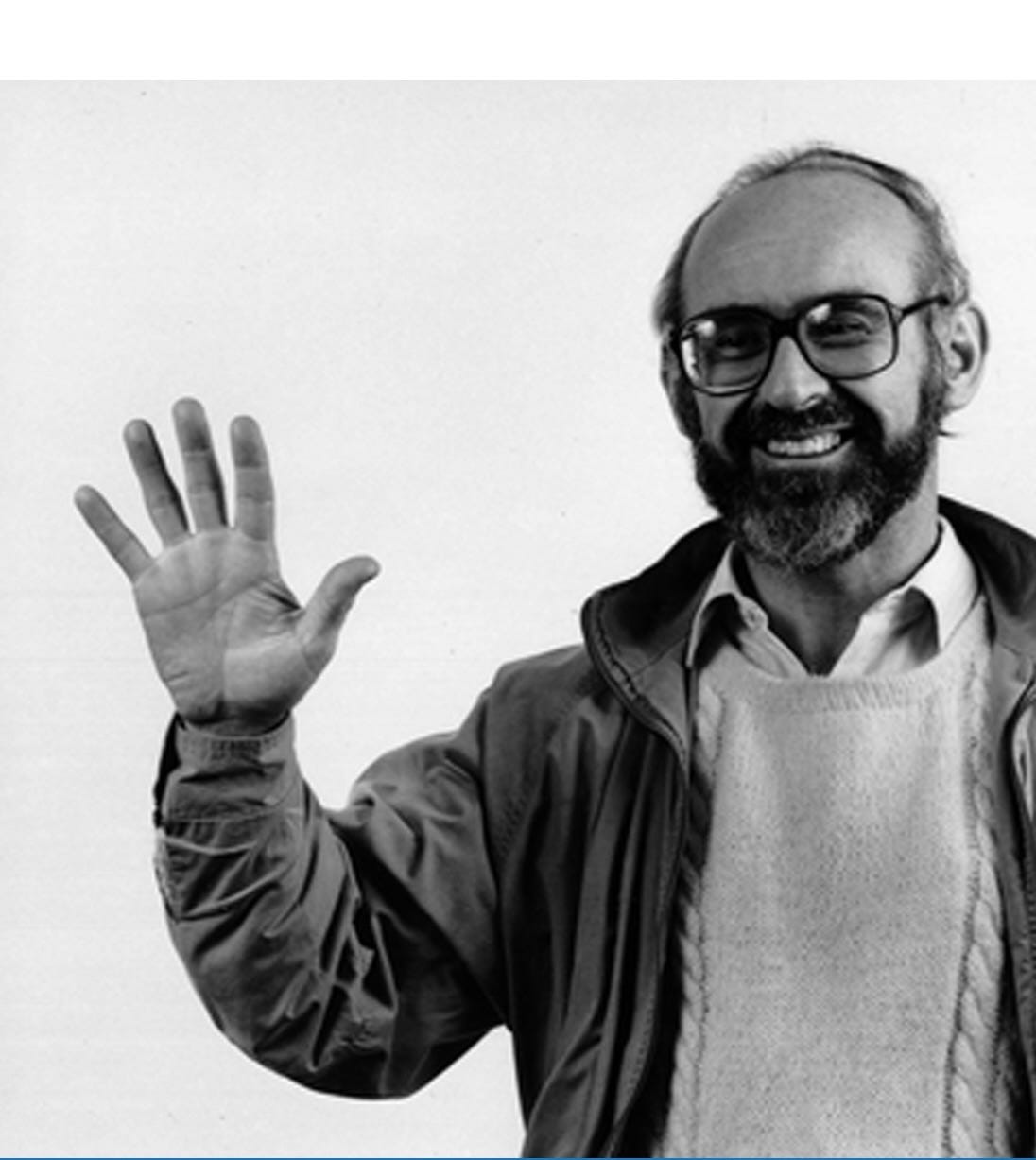

Liberation studies offered us an elegant solution. Please meet Fr. Ignacio Martin-Baro, one of the founders of Liberation Psychology.

He was a social psychologist and Jesuit priest in El Salvador, and he was murdered by a death squad on November 16, 1989. (I was in the Jesuit Volunteer Corps at the time.) Much later I read translations of his essays, Ignacio Martin-Baro's Writings for a Liberation Psychology (edited by Adrianne Aron and Shawn Corne, Harvard University Press, 1994). Here’s a quote:

"The dominant models in psychology are founded on a series of assumptions that are rarely discussed, and even more rarely are alternatives to them proposed...if we want psychology to make a significant contribution...we have to redesign our theoretical and practical tools, but redesign them from the standpoint of our own people: from their sufferings, their aspirations, and their struggles."

Most acupuncture schools, including the one I went to, prioritize teaching the theories of acupuncture, particularly the set of theories known as Traditional Chinese Medicine, which was systematized in 1958 by a committee of the People’s Republic of China. I was taught to approach each patient as a problem to be solved according to the logic of TCM theory. If I couldn’t make the theory fit, that was my fault — and if the application of the theory didn’t offer the patient any actual relief, then that was the patient’s fault.

Nobody ever suggested that I could question the value of the theory itself. Like, maybe acupuncture theory wasn’t the most important part of treating a patient, let alone a whole community. In his essays, Fr. Martin-Baro writes about the relationship of practice and theory in psychology. True practice has primacy over true theory, he states, and actions are more important than affirmations.

If you apply the lens of liberation studies to acupuncture, what you get is the freedom to take the practical needs of people — especially poor and marginalized people — and work backwards to make or re-make acupuncture theory that will work for them. You don’t have to struggle to squeeze them into theories that were developed by people who didn’t know anything about them.

Even better, you can learn about how acupuncture works by making an effort to provide it to people who need it the most; you will learn more from that kind of action than you can learn from any acupuncture textbook. Fr. Martin-Baro says:

"All human knowledge is subject to limitations imposed by reality itself. In many respects that reality is opaque, and only by acting upon it, by transforming it, can a human being get information about it... it is necessary to involve ourselves in a new praxis, an activity of transforming reality that will let us know not only about what is but also about what is not, and by which we may try to orient ourselves toward what ought to be."

Or: acupuncture can change the world.

The purpose of our school is to make a space for our students to involve themselves in this kind of praxis. We don’t fit into the rest of the healthcare system (or the rest of the acupuncture profession) but we’re not aiming to. We’re trying to make our own reality, one where acupuncture is available to anybody who needs it. We don’t always succeed but trying represents the best kind of freedom.