As many of you know, the credential that our acupuncture school offers is a Master’s level certificate in Liberation Acupuncture. As the only accredited Liberation Acupuncture school, we’re always working on explaining what that means. (See also Liberation Acupuncture Part One and Part Two.) The concept of liberation acupuncture originates with liberation theology, which people like Paul Farmer have applied to public health in general.

Recently I had a great conversation with Jamila Wilson, who’s in the second year of POCA Tech’s program. It’s not typical for students to come in with background experience of liberation theology, but Jamila did, and I’m delighted that she wanted to share her perspective on both the academic and practical aspects of liberation acupuncture.

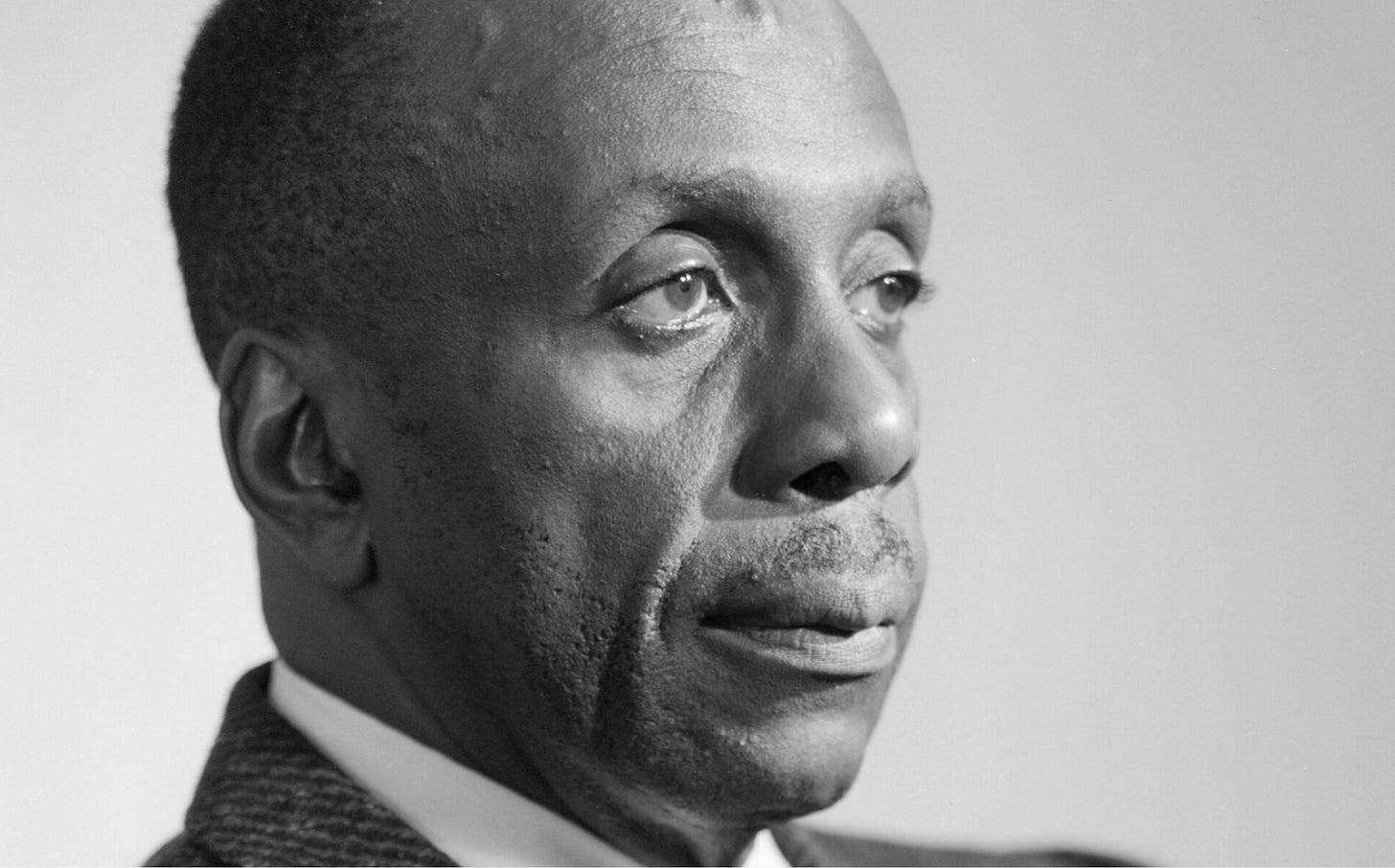

Jamila: I see liberation acupuncture as a continuation of liberation theology. My first exposure and experience with liberation theology was through James Hal Cone, a theologian who sought to find a balance, or an intersection, between Martin Luther King and Malcolm X — and through his book, Black Theology and Black Power.

I grew up in the Black church, particularly the United Methodist Church, because my father is a United Methodist minister. There was always an emphasis placed upon a liberation perspective when it came to our practice of Christianity, and of course King was a huge example, or figure, within that. But it was much later that I became aware of the work of Howard Thurman.

I knew of him as a mentor of King when he was at Boston University, and through that mentorship the awareness of Gandhi’s work and the nonviolent resistance movement in India. But I didn’t really understand yet how foundational he was.

In 1944 he helped establish the first racially integrated, intercultural, and interfaith church in the United States, the Church for the Fellowship of All Peoples, in San Francisco, California. Jesus and the Disinherited, published in 1949, is one of his most important works.

Here’s a description in his own words:

“MANY and varied are the interpretations dealing with the teachings and the life of Jesus of Nazareth. But few of these interpretations deal with what the teachings and the life of Jesus have to say to those who stand, at a moment in human history, with their backs against the wall…I do not ignore the theological and metaphysical interpretation of the Christian doctrine of salvation. But the underprivileged everywhere have long since abandoned any hope that this type of salvation deals with the crucial issues by which their days are turned into despair without consolation. The basic fact is that Christianity as it was born in the mind of this Jewish teacher and thinker appears as a technique of survival for the oppressed. That it became, through the intervening years, a religion of the powerful and the dominant, used sometimes as an instrument of oppression, must not tempt us into believing that it was thus in the mind and life of Jesus. “In him was life; and the life was the light of men.” Wherever his spirit appears, the oppressed gather fresh courage; for he announced the good news that fear, hypocrisy, and hatred, the three hounds of hell that track the trail of the disinherited, need have no dominion over them.”

He recounts his experiences in India in the 1930s, including one conversation he had with a Hindu scholar, who was curious as to why this Black American was in India talking about Christianity, knowing the historical experience that Black people had in America. He basically asked, What’s your intention? Why are you spreading this Gospel when it’s been used to oppress your people?

Howard Thurman was intrigued by the question, and he notes that it helped him come to one of the central metaphors of the book, the idea of the people “who stand with their backs against the wall”. He turns toward an understanding of the historical Jesus, Jesus as subject rather than object. Jesus amongst the poor, under an oppressive Roman regime.

Me: I think that’s one of the key aspects of any kind of liberation studies: a focus on historical context.

Jamila: Our first year at POCA Tech when we were introduced to liberation acupuncture and its origins with liberation theology, Felicia taught it from the perspective of theologians in Latin America, which I had not had any exposure to previously. Since then I’ve been researching and trying to find support for the possibility that there could have been interactions between those scholars and theologians and Howard Thurman’s work.

The beginning of liberation theology as a movement is usually associated with the second Latin American Bishops’ Conference in Medellin, Colombia in 1968, and the documents produced there. The main text, A Theology of Liberation by Gustavo Gutierrez, was published in 1971. But of course Howard Thurman was writing in the 1940s. It seems like the trajectory of scholarship around liberation theology emerges during this period of oppressed people rising around the world.

I believe that this is the foundation of what liberation theology is seeking to express: the awareness of oppression coupled with the desire to be free.

Me: I really appreciate this introduction to Howard Thurman. This is going to change how we teach the first year introduction to liberation acupuncture.

There’s another quote from Jesus and the Disinherited that I came across:

“Mere preaching is not enough. What are words, however sacred and powerful, in the presence of the grim facts of the daily struggle to survive? Any attempt to deal with this situation on a basis of values that disregard the struggle for survival appears to be in itself a compromise with life. It is only when people live in an environment in which they are not required to exert supreme effort into just keeping alive that they seem to be able to select ends besides those of mere physical survival. “

I think one of the things that speaks to me most about liberation theology is the affirmation that so many people are just trying to survive. Whether you’re a theologian or an acupuncturist, you need to take that into account. Also, talk is cheap, no matter how beautiful the words. You have to think about what you’re offering to the people “who stand with their backs against the wall” — from their perspective.

Jamila: I feel that liberation acupuncture is about removing a kind of veil from the practice of acupuncture. It is a democratizing of this healing modality. In this country, acupuncture has primarily been made available to the professional and ruling class. Liberation acupuncture, similar to liberation theology, positions the participant — the patient — in the seat of power. Through the community acupuncture model that WCA practices, patients are able to access this ancient healing practice on their own terms, in an affordable, community center space, rooted in a trauma informed perspective, and for how long they would like (I find personal joy when patients share they did not intend to fall asleep and they end up resting for up to two hours)!

In Jesus and the Disinherited Howard emphasizes the role fear plays in keeping the oppressed subjugated and under the control of the ruling class.

This is common in conventional western medicine where autonomy and ownership of one's body is not to be managed by the individual, but by the system of medicine. A certain level of fear is layered on top of our experience with the health and medical industry. This takes power away from the individual to lead and account for their own care.

Liberation acupuncture, like liberation theology, empowers the individual to have confidence in their innate goodness and the healing properties the body possesses to support and maintain a healthy and balanced body. Liberation acupuncture prioritizes the human and their experience in their body. Each time that person receives a treatment they are invited to lead the healing process; they become more invested and confident in their body's ability to be strong, healthy, and valued.

Liberation acupuncture provides hope for future systems to experience a revolutionary shift in how we organize and care for ourselves. Liberation theology reminds us that the role of humans on this planet is to love in the face of hate. To challenge the systems of exclusion and elitism with a practice that welcomes all to the table (or recliner) no matter what their background, previous experience with healthcare providers, or whether they deserve care or not, to find rest.

to be continued