Less Gatekeeping, More Sharing Pt 2: Why We Made Our Own Acupuncture School

In the early 2000s there were not many resources for acupuncturists starting their businesses. One of the few books about acupuncture and small business was called Points for Profit: the Essential Guide to Practice Success for Acupuncturists. It’s still considered a classic and it’s a textbook in many acupuncture schools.

Here’s a quote from page 125 of the third edition: “First, it is well known that your personal income will be the same as that of your average patient; (as a result) we suggest that you check out the financial demographics of the town or area in which you plan to set up a clinic...

Second, it is a proven fact that people who are not charged at all or who are charged very low fees rarely get well as quickly and completely as people who are charged more.”

A proven fact. Really? The biological mechanisms for acupuncture aren’t fully understood -- yet somehow there’s a directly proportional relationship between cost and efficacy? Can I see the research that proves that? And what does “get well quickly and completely” actually mean, especially for people with chronic illnesses?

When I first read statements like this, I thought, I live in Cully and I want to treat people like my neighbors. My grandfather was a gas station attendant and I want to treat people like my family. Where does this kind of logic leave somebody like me? Another acupuncture marketing website encouraged practitioners: “Don’t be afraid to raise your prices -- when you raise your prices, you will attract a better quality of patient.”

Yeah, this is why we have a big red fist on the side of our building.

And this is also the first reason why we had to make our own acupuncture school -- because existing schools were teaching students that patients get better clinical outcomes when you charge them more.

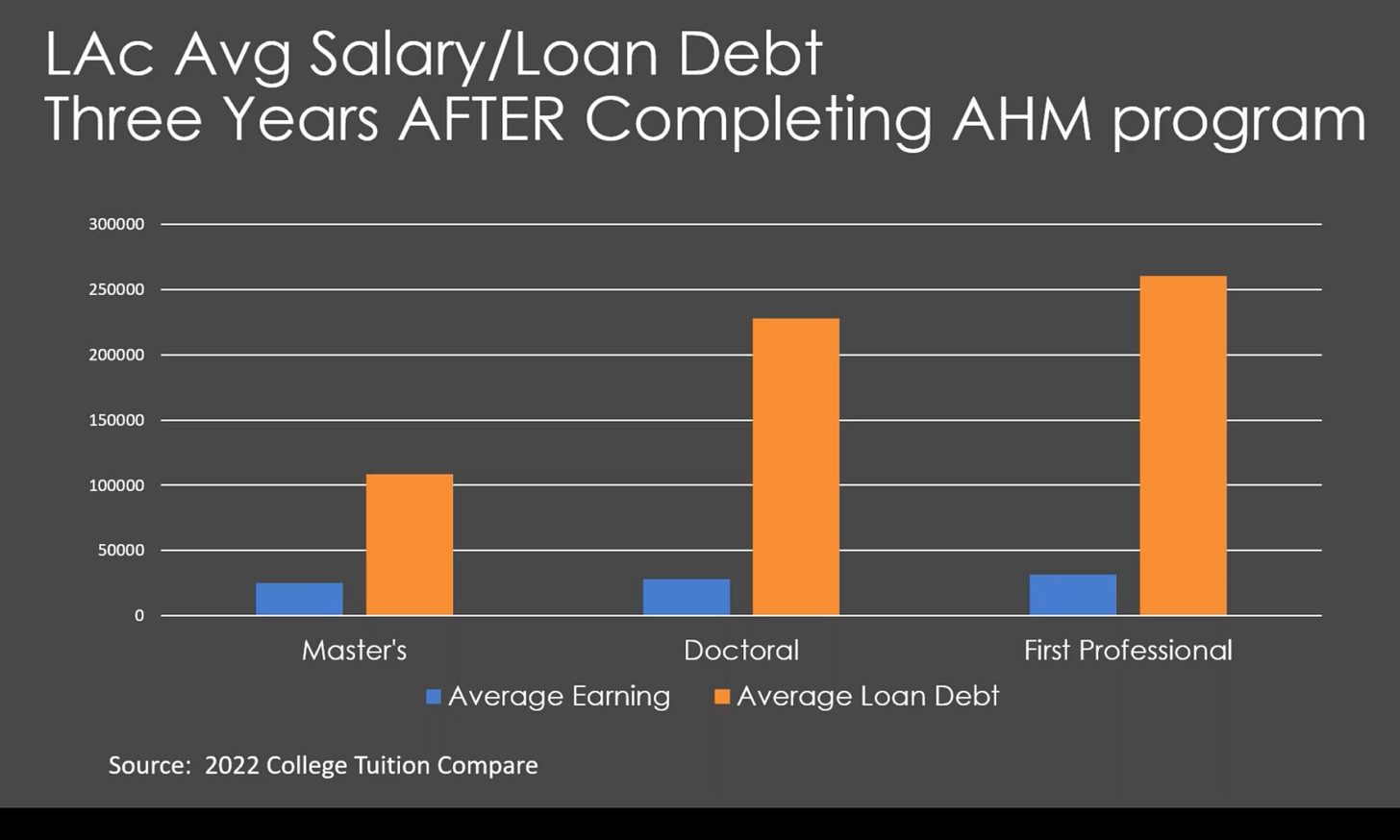

But let’s return to what acupuncturists earn. When I read that I should expect to earn what my patients earn, I thought that sounded like a threat but also, a challenge. FINE, I accept your challenge, you classist twits! And I did indeed go on to earn my living, and also find enormous satisfaction, in serving my working class community. I had no idea, though, that there were huge problems with what acupuncturists earn even if they weren’t determined to practice in a neighborhood like Cully. Take a look at this graph, which was released in 2022 and is based on research by the American Society of Acupuncturists:

You might have to expand the graphic to really see it, but it looks an awful lot like acupuncturists are earning on average about $30,000 a year, three years after getting out of acupuncture programs that saddled them with an average of $100,000 to over $250,000 in student loan debt. This research didn’t target acupuncturists working in community clinics, it was aimed at all acupuncturists (including the ones treating “a better quality of patients”), and it tracks with other research about acupuncturists’ incomes. In another survey by the California Acupuncture Board (the majority of acupuncturists in the US live in California), 41% of respondents said they “did not feel able to earn a living wage as a licensed acupuncturist”.

By the time WCA had three clinics, obviously we needed acupuncturists to staff them. We knew there was a huge discrepancy between what acupuncture school costs and what an acupuncturist working at WCA (or most other places) would earn.

That’s the second reason why we had to make our own acupuncture school -- we didn’t want to ask prospective community acupuncturists to take on hundreds of thousands of dollars in student loan debt.

If we wanted WCA to have a future, we needed an acupuncture school with tuition costs that were dramatically lower, and nobody was going to make that school FOR us. So we made our own school, in partnership with the POCA Cooperative (that’s the People’s Organization of Community Acupuncture) which is why the school’s name is POCA Tech. One of the valuable elements of our recent coaching work with Camille Trummer was recognizing the organizational partnerships that WCA already has, and the school is at the top of that list. Ten years after opening the school, about 60% of WCA acupuncturists are also POCA Tech graduates. WCA couldn’t do what it does without POCA Tech!

POCA Tech tuition is $20,000 for a three year Master’s-level program. For comparison purposes, the tuition for acupuncture Masters’ programs at the two other acupuncture schools in Portland, OCOM and NUNM, is about $71,000 and $77,000 respectively. We also designed the program in modular form so that students could work throughout the program; you can see from the graph that graduates of Master’s-level programs get out of school with over $100,000 in debt as a result of needing to borrow money for living expenses.

The question is, at what price point is acupuncture education a reasonable investment as opposed to a bad, maybe terrible, financial decision?

This statement will not make me popular, but: Given the data about what acupuncturists earn, it looks like that point is about $30,000, give or take. How difficult it is to make those numbers work for POCA Tech itself is a topic for a whole other post. What I’m trying to get at here is that the dominant paradigm for acupuncture education is thoroughly broken and it wasn’t an option for WCA to ask future employees to participate in it.

The third reason that we had to make our own acupuncture school gets us back to the image of the Well. When other schools are encouraging prospective students to sign on the dotted line for student loans, they frame the cost of acupuncture education as an individual investment which will pay off in the future. One school put it this way: “An acupuncture degree can be a valuable, long-lived asset that produces a life-long income stream and an eventual capital asset (a practice) that can be sold. In the business world, the decision to invest or not invest in a business opportunity is commonly made based on comparing the amount invested now with the total returned in the future. Further, companies realize that taking on some debt (leverage) can be financially wise under some conditions. Usually, the company is short of cash to fund the project in the short term but expects to be able to use the asset to generate more than the amount invested in the future. Borrowing to attend graduate school is a similar proposition. The optimal amount of debt undertaken depends on the entire future stream of income that the investment will produce, not just the original amount of debt.”

Given what the research shows about acupuncturists’ “future stream of income” this is a questionable proposition. Also, an acupuncture degree is only an economic asset if you can build an acupuncture business, otherwise it’s a worthless piece of paper. Future practitioners, the same ones who are supposed to help retiring practitioners cash out their investment, are already drowning in debt from their own education and obviously not in a position to purchase a practice -- let alone at a price that would justify the seller’s student loan burden. But the bigger issue for WCA is the way that students are taught to approach acupuncture NOT as a community resource but as a special individual benefit for lucky (wealthy) individuals who live in well-off neighborhoods and as the basis for a future “capital asset”. That’s just not how we think about the value of acupuncture.

We introduce POCA Tech students to the value of organizational partnerships while they’re in school. This past weekend, longtime WCA Board member Lisa Achilles taught a class to our second year students about working with public health clinics.

Lisa was one of the original public health case managers who helped set up WCA’s relationship with Care Oregon; that relationship has been benefiting both organizations since 2012, and now it benefits POCA Tech students as well. Just like WCA couldn’t do what it does without POCA Tech, the school couldn’t train the next generation of community acupuncturists without the support of committed volunteers like Lisa. I can’t overstate what it means for us at WCA when people like Lisa, who come from outside the acupuncture profession, believe in the value of community acupuncture — because people INSIDE the acupuncture profession generally don’t.

Expensive acupuncture education is like expensive acupuncture treatments -- it’s a form of gate-keeping. We believe that people should be able to become acupuncturists without having to mortgage their futures as a price of admission. But we need partnerships, and we need people who believe in us, in order to do it.